Understanding Medicaid Home and Community Services: A Primer 2010 Edition

2010 Edition

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services

Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services

Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation

200 Independence Avenue, Washington, DC 20201

Understanding Medicaid

Home and Community Services:

A Primer

Oce of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation

The Oce of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation (ASPE) is the principal advisor to the Secre-

tary of the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) on policy development issues, and is responsible

for major activities in the areas of legislative and budget development, strategic planning, policy research and

evaluation, and economic analysis.

ASPE develops or reviews issues from the viewpoint of the Secretary, providing a perspective that is broader

in scope than the specic focus of the various operating agencies. ASPE also works closely with the HHS

operating divisions. It assists these agencies in developing policies, and planning policy research, evaluation

and data collection within broad HHS and administration initiatives. ASPE often serves a coordinating role for

crosscutting policy and administrative activities.

ASPE plans and conducts evaluations and research—both in-house and through support of projects by ex-

ternal researchers—of current and proposed programs and topics of particular interest to the Secretary, the

Administration and the Congress.

Oce of Disability, Aging and Long-Term Care Policy

The Oce of Disability, Aging and Long-Term Care Policy (DALTCP), within ASPE, is responsible for the develop-

ment, coordination, analysis, research and evaluation of HHS policies and programs which support the inde-

pendence, health and long-term care of persons with disabilities—children, working aging adults, and older

persons. DALTCP is also responsible for policy coordination and research to promote the economic and social

well-being of the elderly.

In particular, DALTCP addresses policies concerning: nursing home and community-based services, informal

caregiving, the integration of acute and long-term care, Medicare post-acute services and home care, man-

aged care for people with disabilities, long-term rehabilitation services, children’s disability, and linkages

between employment and health policies. These activities are carried out through policy planning, policy and

program analysis, regulatory reviews, formulation of legislative proposals, policy research, evaluation and data

planning.

This report was prepared under contract #HHS-100-03-0025 between HHS’s ASPE/DALTCP and RTI International.

For additional information about this subject,

you can visit the DALTCP home page at

http://aspe.hhs.gov/_/oce_specic/daltcp.cfm

or contact the ASPE Project Ocer,

Emily Roseno, at HHS/ASPE/DALTCP

Room 424E, H.H. Humphrey Building,

200 Independence Avenue, S.W., Washington, D.C. 20201

Her e-mail address is: Emily.Roseno@hhs.gov

Understanding Medicaid

Home and Community Services: A Primer

2010 Edition

Project Director

Janet O’Keee

Co-Authors

Janet O’Keee

Paul Saucier

Beth Jackson

Robin Cooper

Ernest McKenney

Suzanne Crisp

Charles Moseley

Managing Editor

Christine O’Keee

ASPE Project Ocer

Emily Roseno

Dear Reader,

We are pleased to present this updated version of the Medicaid Home and Community

Services Primer. Over the past 10 years, the Primer has fullled its primary purpose of in-

forming key stakeholders about the statutes and regulations governing the nancing and

provision of Medicaid home and community services. Specically the Primer was designed:

• To explain how the Medicaid program can be used to expand access to a broad range

of home and community services and supports for people of all ages with disabilities,

and to promote consumer authority and control over their services; and

• To encourage a fundamental approach to the support of people with disabilities that

minimizes reliance on institutions and maximizes community integration in the most

cost-eective manner.

Medicaid policy has continued to evolve over the last 10 years to better support options

for community living by people of all ages with disabilities and/or chronic health condi-

tions. The Decit Reduction Act of 2005 and the Patient Protection and Aordable Care

Act of 2010 both created new options for states to provide home and community services

without having to secure a federal waiver. In addition, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid

Services (CMS) has made numerous changes to the program to make it easier for individu-

als to live in the community, such as authorizing coverage of one-time transition expenses

for home and community-based services (HCBS) waiver participants.

The current edition of the Primer has been updated to include all relevant statutory, regula-

tory and other policy changes that have occurred in the last 10 years. Given the signicance

of the recent changes in Medicaid, I believe the Primer will be an ever more useful tool for

all those working to ensure that people with disabilities can live in the most integrated set-

tings appropriate to their needs.

This updated version of the Primer would not have been possible without the commitment

and hard work of many people. In particular I want to recognize and thank the CMS sta

who took time out of their busy schedules to review each chapter of the Primer to ensure

that the content was accurate and consistent with current policy.

As the Medicaid program continues to evolve to better meet the needs of its beneciaries,

new policy and clarications of existing policy will be made subsequent to the publication

of the Primer. Information about policy changes will be disseminated through State Medic-

aid Director Letters, the Federal Register, and the State Medicaid Manual, which are avail-

able on the CMS website.

Richard Frank

Deputy Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation

Disability, Aging, and Long-Term Care Policy

DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH & HUMAN SERVICES Oce of the Secretary

Washington, D.C. 20201

Acknowledgments

ASPE acknowledges with gratitude the assistance

of the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services

in completing the revised Primer. In particular, we

would like to thank CMS sta who reviewed each

chapter to ensure technical accuracy and consis-

tency: Mary Sowers, Roy Trudel, Dan Timmel, Kathy

Poisal, Carey Appold, Peggy Clark, Carrie Smith, El-

len Blackwell, Melissa Harris, Anita Yuskauskas, and

Kenya J. Cantwell. We also thank CMS for funding

the development of the appendix on quality man-

agement systems.

Table of Contents

Introduction

The 2010 Edition of the Primer ........................................................................................................................ 13

Chapter 1

Medicaid Coverage of Home and Community Services: Overview ................................................... 19

Chapter 2

Financial Eligibility Rules and Options .......................................................................................................... 37

Chapter 3

Determining Service Eligibility ........................................................................................................................ 63

Chapter 4

Options for Designing Service Coverage: General Considerations .................................................... 85

Chapter 5

Providing Medicaid Services in Community Residential Settings ....................................................123

Chapter 6

Transitioning People from Institutions to the Community .................................................................151

Chapter 7

Participant-Directed Services and Supports ............................................................................................175

Chapter 8

Medicaid Authorities for Delivering Home and Community

Services through Risk-Based Managed Care Systems ..........................................................................211

Appendix:

Medicaid HCBS Quality ....................................................................................................................................231

11

Introduction to the 2010 Edition of the Primer

Dedication

Gary Smith, the principal author of the original Primer,

died in November 2007.

Gary was the preeminent expert on Medicaid Policy and

was a resource to hundreds of people all over the country:

researchers, policymakers, Centers for Medicare & Medic-

aid Services sta, state sta, and advocates. He was always

generous with his time and his expertise and never let a

request for help go unanswered. He is greatly missed—as

a colleague and a friend.

Although millions of people with disabilities have never

heard his name, his work in public policy has made an

ongoing positive dierence in their lives.

We dedicate this edition of the Primer to his memory.

13

Introduction to the 2010 Edition of the Primer

Introduction to the 2010 Edition of the Primer

The Primer was rst published in 2000—one year after the Supreme Court decision in Olmstead v. L.C. af-

rmed the right of persons with disabilities to live in the most integrated setting (see Box).

1

A major purpose of

the original Primer was to provide information about how the Medicaid program could be used to assist states

in meeting the principles set out in the Olmstead decision.

In the 10 years since the Primer was published, Medicaid policy regarding the provision of home and commu-

nity services has evolved considerably. During this period, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS)

awarded hundreds of grants to support states’ eorts to improve access to—and the availability and quality

of—home and community services. The grants were also aimed at increasing Medicaid participants’ control

over their services and supports.

2

The Olmstead Decision

3

The Supreme Court ruled that “Unjustied isolation . . . is properly regarded as discrimination based on disability.”

It observed that (a)“institutional placement of persons who can handle and benet from community settings

perpetuates unwarranted assumptions that persons so isolated are incapable or unworthy of participating in

community life,” and (b)“connement in an institution severely diminishes the everyday life activities of individu-

als, including family relations, social contacts, work options, economic independence, educational advancement,

and cultural enrichment.”

Under the Court’s decision, states are required to provide community-based services for persons with disabilities

who would otherwise be entitled to institutional services when (a)the state’s treatment professionals reason-

ably determine that such placement is appropriate; (b)the aected persons do not oppose such treatment; and

(c)the placement can be reasonably accommodated, taking into account the resources available to the state and

the needs of others who are receiving state-supported disability services. The Court cautioned, however, that

nothing in the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) condones termination of institutional settings for persons

unable to handle or benet from community settings. Moreover, the state’s responsibility, once it provides

community-based treatment to qualied persons with disabilities, is not unlimited.

Under the ADA, states are obliged to “make reasonable modications in policies, practices, or procedures when

the modications are necessary to avoid discrimination on the basis of disability, unless the public entity can

demonstrate that making the modications would fundamentally alter the nature of the service, program or ac-

tivity.” The Supreme Court indicated that the test as to whether a modication entails “fundamental alteration” of

a program takes into account three factors: the cost of providing services to the individual in the most integrated

setting appropriate, the resources available to the state, and how the provision of services aects the ability of

the state to meet the needs of others with disabilities.

The rst edition of the Primer emphasized that people of all ages with disabilities want the same opportunities

that every American wants: to thrive, not just survive. They want to live in their own homes and make deci-

sions about daily activities; they want to go to school, attend church services, work, and participate fully in

recreational and other community activities. People with disabilities have not always been allowed this birth-

right; society has too often focused on their disabilities rather than their abilities.

Over the past 2 decades, and particularly since the Olmstead decision, progress has been made. People with

disabilities are now recognized as being able to live in their own homes and other community settings, and to

14 Understanding Medicaid Home and Community Services: A Primer

lead satisfying and productive lives when provided

with appropriate services and supports. Much re-

mains to be done to enable all persons with disabili-

ties to do so.

Medicaid: An Evolving Program

with Considerable State Flexibility

Medicaid is the major source of public funding for

long-term services and supports provided in home

and community settings. Medicaid was enacted

in 1965 as a companion program to Medicare.

4

It

was designed as a joint Federal-state entitlement

providing primarily medical care to low-income

Americans.

5

When rst enacted, Federal Medicaid

funding for meeting long-term care needs was

available mainly when individuals were placed in an

institution (e.g., a nursing home), with few avenues

for supporting them in their homes and communi-

ties. State funds were used to pay for “home care”

programs, but only on a limited basis.

6

In the 45 years since its enactment, Medicaid’s “insti-

tutional bias” has been steadily diminished through

numerous amendments to Federal laws and policy.

Since the early 1980s, there has been a steady

increase in the options available to states to secure

Federal Medicaid funding for comprehensive home

and community services. The Decit Reduction Act

of 2005 (DRA-2005) authorized a new optional State

Plan authority for states to provide home and com-

munity-based services (HCBS) without a waiver, and

most recently, the Patient Protection and Aordable

Care Act (hereafter referred to as the Aordable

Care Act), enacted in 2010, authorized an additional

optional State Plan authority to provide “Communi-

ty-based Attendant Services and Supports”—called

the Community First Choice Option.

Over the past two decades, states have greatly

expanded the availability of home and community

services. The portion of Medicaid long-term care

spending directed to home and community ser-

vices has been increasing steadily by one to three

percentage points each year as states continue to

invest more resources in alternatives to institutional

care. In 2009, home and community services ac-

counted for 45 percent of total Medi caid long-term

care spending.

7

Many states are using innovative

and scally responsible methods to enable more

persons with disabilities to receive necessary ser-

vices in their communities instead of in institutions.

The Medicaid program provides many options to

increase the availability of home and community

services while controlling costs. As states work

toward the goal of integrating people of all ages

with all types of disabilities into their communities,

they may need to go through a process of funda-

mentally rethinking how programs serving people

with disabilities are structured and how resources

are allocated.

The chapters in this Primer stress that when de-

ciding how best to use the Medicaid program to

expand the provision of home and community

services, states need to consider their unique needs,

resources, and social, political, and economic envi-

ronments. Additionally, all of these factors must be

considered in the context of the technological and

demographic changes driving the need for publicly

funded long-term care services and supports.

Key among these changes are advances in medical

technology that have enabled increasing numbers

of people with congenital and acquired disabili-

ties to both survive and live longer lives. A second

change is that the nation’s population is aging. The

group most likely to need long-term care—people

over age 85—is estimated to grow from 5.3 million

in 2006 to nearly 21 million by 2050.

8

Moreover, the aging population includes individuals

who have spent their lives providing informal care

for adult children with intellectual disabilities and

other developmental disabilities (ID/DD, hereafter

referred to as developmental disabilities). Now that

many individuals with developmental disabilities

are outliving their parents, an increase in the num-

ber needing services and support is expected in the

coming years.

10

Finally, most assistance to people

with disabilities is provided by informal caregivers,

typically women. However, continued reliance on

this support in the coming years may be unrealistic,

given high rates of women’s labor force participa-

tion, smaller families, and geographic mobility.

15

Introduction to the 2010 Edition of the Primer

Terminology and Denitions

In this Primer, the term “persons with disabilities” includes persons of all ages—young children, adolescents,

and working age or older adults—with all types of disabilities due to physical and mental impairments and/or

chronic illnesses. Because the Primer’s focus is on Medicaid home and community services, the term “people with

disabilities” refers primarily to those individuals who need long-term care services. However, not all persons with

disabilities need these services.

The service systems for dierent disability groups use dierent terms for the same or similar services. For exam-

ple, the service system for older adults uses long-term care or long-term care services, whereas the service sys-

tem for people with developmental disabilities uses long-term services and supports or just supports. States also

vary in their use of terms: personal care is also called personal assistance or attendant care, which is provided by

personal care providers, personal assistants, personal attendants, and direct care workers, among other names.

To eliminate confusion, the Primer uses terms consistently in all chapters and specically notes when terms are

used interchangeably. When discussing a particular state’s service system, or Federal statutes and regulations,

the Primer uses the specic terms they use. For example, the term home and community-based services is used

only when referring to Federal statutes, regulations, or programs that use this term. In general, the Primer uses

the term home and community services or just services and supports.

A law enacted in October 2010 amended provisions of Federal law to substitute the term “an intellectual disabil-

ity” for “‘mental retardation,” and “individuals with intellectual disabilities” for “the mentally retarded” or “indi-

viduals who are mentally retarded.”

9

Intermediate Care Facilities for Persons with Intellectual Disabilities (ICF/

ID) is the new title for the program formerly known as Intermediate Care Facilities for the Mentally Retarded. The

Primer uses these new terms, except when the former terms are used in the titles of previously published books,

reports, and articles.

To ensure brevity without excessive use of acronyms when referring to systems of care, the Primer generally uses

the shortest term (e.g., long-term care rather than long-term care services and supports).

Finally, many of the Medicaid provisions discussed in the Primer were enacted when the Centers for Medicare &

Medicaid Services was known as the Health Care Financing Administration (HCFA). Throughout the Primer, the

current name—CMS—will be used, even when referring to actions the agency made when it was named HCFA.

16 Understanding Medicaid Home and Community Services: A Primer

Purpose, Audience, and

Organization of the Primer

Medicaid oers a complex and varied set of home

and community service options—with similarly

complex rules and regulations—that can be bewil-

dering for policymakers, state ocials, advocates,

and consumers. Even people who have spent years

working in Medicaid state agencies do not always

understand its many provisions. The extensive

exibility states have to combine these options has

resulted in considerable variation among states’

Medicaid programs. As some wit has put it, “What

state Medicaid programs have most in common is

that they are all dierent.”

The Primer is designed to encourage states to use

the Medicaid program to minimize reliance on

institutions and maximize community integra-

tion for people with disabilities in a cost-eective

manner. Its intended audience is policymakers,

state Medicaid sta, and all stakeholders who wish

to understand how Medicaid can be used—and is

being used—to expand access to a broad range of

home and community services and supports. In ad-

dition to providing comprehensive explanations of

Medicaid home and community service options, the

Primer presents examples of states that have used

them to promote greater community integration of

people with disabilities.

The service options reviewed address program

modications that states can implement as a State

Plan option (without a special waiver of Federal

law), as well as those for which Federal waiver ap-

proval must be obtained. While each chapter has

been written to cover a specic topic, and as such,

can be read independently of the rest of the Primer,

it also assumes an understanding of basic Medicaid

terms and provisions, such as comparability and

statewideness, mandatory and optional services,

State Plan and waiver services. Those unfamiliar

with these basic terms should rst read Chapter 1.

When a topic is covered in depth in one chapter,

that chapter will be referenced in other chapters

that address the topic.

Chapter 1 provides a brief overview of the legisla-

tive and regulatory history of Medi caid’s cover-

age of home and community services and current

spending on these services.

The next two chapters describe the basic elements

of Medicaid’s nancial and service eligibility criteria.

Chapter 2 provides an explanation of Medi caid’s

nancial eligibility criteria, a complex area of Med-

icaid law. It rst discusses the general eligibility

criteria that all Medicaid beneciaries must meet. It

then focuses on the nancial eligibility provisions

most important for receiving services in home and

community settings. The chapter also reviews the

options states can select to ensure that people with

disabilities can support themselves in home and

community settings.

Chapter 3 focuses on Medicaid provisions related

to the health and functional criteria states use to

determine eligibility for State Plan home health

services, State Plan personal care services, State Plan

home and community-based services, and HCBS

waiver programs. The chapter also discusses how

states can design service criteria to ensure that they

appropriately and adequately measure the need

for services and supports among heterogeneous

populations.

Chapters 4 and 5 describe service coverage options.

Chapter 4 presents the major service options for

providing home and community services to people

with disabilities. The factors states need to consider

when choosing among the various options are also

discussed.

Chapter 5 describes coverage options for providing

services in a wide range of residential care settings

that are provider-owned and/or operated, including

foster care, group homes, and assisted living.

Chapters 6 and 7 focus on key policy goals related

to coverage of home and community services.

Chapter 6 discusses factors states need to consider

when developing initiatives to transition institu-

tional residents to home and community settings. It

also presents ways in which Medicaid can be used

to facilitate transitions.

17

Introduction to the 2010 Edition of the Primer

Chapter 7 describes Medicaid options to increase

participants’ choice and control of home and com-

munity services.

Chapter 8 describes options for states to provide

Medicaid home and community services through

managed care delivery systems.

An appendix provides an overview of CMS require-

ments for quality management and improvement

systems for HCBS waivers.

To make the Primer as useful as possible, each chap-

ter includes a Resources section that provides infor-

mation about key publications and links to websites

from which the reader can obtain more detailed

information about the chapter’s topic. The endnotes

for each chapter include not just source citations,

but additional technical information and—in many

cases—web links to these citations and information.

Thus, while the Primer can be read either in hard

copy or online, the online version enables readers to

access a considerable amount of additional infor-

mation.

This Primer has been prepared by the Oce of the

Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation in

the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services,

and reviewed for accuracy by CMS sta. Designed

to serve as a reference guide, it is written in easily

understood language, but with sucient annota-

tion of source material to fulll its technical support

function.

18 Understanding Medicaid Home and Community Services: A Primer

Endnotes

Citations, Additional Information, and Web Addresses

1

Olmstead v. L. C., 119 S.Ct. 2176 (1999).

2

The grants were implemented through several programs, primarily the Systems Change Grants for Commu-

nity Living program.

3

The Olmstead decision interpreted Title II of the ADA and its implementing regulations, which oblige states

to administer their services, programs, and activities “in the most integrated setting appropriate to the needs

of qualied individuals with disabilities” (28 CFR 35.130(d)). Information about the application of the Olm-

stead decision to the Medicaid program is available from the CMS website in State Medicaid Director Letters.

Available at http://www.cms.hhs.gov/SMDL/SMD/list.asp#TopOfPage. Use the word Olmstead to nd the

relevant letters.

4

P.L. 89-97, Title XIX of the Social Security Act.

5

The Federal Government provides matching funds on an open-ended basis for every dollar a state chooses

to spend on Medicaid services.

6

Federal funding through specic programs was sometimes available.

7

Citation: Eiken, S., Sredl, K., Burwell, B., and Gold, L. (2010). Medicaid Long-Term Care Expenditures in FY 2009.

Cambridge, MA: Thomson Reuters. Available at http://www.hcbs.org/moreInfo.php/doc/3326.

8

U.S. Agency on Aging. Statistics available at http://www.aoa.gov/agingstatsdotnet/Main_Site/Data/2008_

Documents/Population.aspx.

9

Called Rosa’s Law (Bill S.2781), signed October 5, 2010, by President Barack Obama.

10

Hubert, J., and Hollins, S. (2002). People with Intellectual Disabilities and Their Elderly Caregivers.

Available at http://www.intellectualdisability.info/life-stages/people-with-intellectual-disabilities-and-their-

elderly-carers/?searchterm=People%20with%20Intellectual%20Disabilities%20and%20Their%20Elderly%20-

Caregivers.

Chapter 1: Medicaid Coverage of Home and Community Services: Overview

19

Guide to Chapter 1

Introduction . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 21

Program Evolution and Current Spending Allocations . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 21

Major Features of Medicaid’s Provisions for Home and Community Services . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 23

Mandatory State Plan Services: Home Health . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 23

Mandatory State Plan Services: EPSDT . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 25

Optional State Plan Services: Personal Care . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 25

Optional State Plan Services: Targeted Case Management . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 26

Optional State Plan Home and Community-Based Services . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 27

Optional State Plan Services: Community Choice Option . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .27

Other Optional State Plan Home and Community Services . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 27

The HCBS Waiver Authority . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 28

The Katie Beckett Provision . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 29

The Program of All-Inclusive Care for the Elderly (PACE) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 30

Resources. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .31

Endnotes: Citations, Additional Information, and Web Addresses . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 35

21

Chapter 1: Medicaid Coverage of Home and Community Services: Overview

Chapter 1

Medicaid Coverage of Home and Community Services: Overview

Long-term care includes a broad range of health and health-related services, personal care, social and

supportive services, and individual supports. These services can be provided in institutions, an individual’s

home, or in community settings. This chapter recounts the legislative, regulatory, and policy history of

Medicaid coverage of long-term care services and supports. Both institutional care and home and com-

munity services are described, with the latter in greater detail.

1

Introduction

Medicaid is a needs-based, entitlement program that is designed to help states meet the costs of necessary

health care for low-income and medically needy populations. When a Medicaid State Plan is approved by the

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), states qualify to receive Federal matching funds to nance

Medicaid services (see Box). States have substantial exibility to design their programs within broad Federal

requirements related to eligibility, services, program administration, and provider compensation.

Federal Medical Assistance Percentage (FMAP)

The Federal government’s share of medical assistance expenditures under each state’s Medicaid program, known

as the Federal medical assistance percentage, is determined annually by a formula that compares

the state’s average per capita income level with the national average. States with higher per capita incomes are

reimbursed smaller shares of their costs. By law, FMAP cannot be lower than 50 percent or higher than 83 per-

cent. States are also reimbursed for 50 percent of administrative costs. For scal year 2009, the

FMAP ranged from 50 percent in California and several other states to 75.84 percent in Mississippi.

2

Program Evolution and Current Spending Allocations

When enacted, Medicaid was the medical care extension of Federally-funded programs providing cash assis-

tance for the poor, with an emphasis on dependent children and their mothers, elderly persons, and persons

with disabilities. Legislation in the 1980s expanded Medicaid coverage of low-income pregnant women and

poor children, and extended coverage to some low-income Medicare beneciaries who were not eligible for

cash assistance. From its beginnings as a health care nancing program primarily for welfare recipients, the

Medicaid program has been amended and expanded to cover a wide range of populations and services.

When rst enacted, Medicaid’s main purpose was to cover primary and acute health care services, such as doc-

tor visits and hospital stays. Mandatory coverage for long-term care was limited to skilled nursing facility (SNF)

services for people age 21 or older. States were given the option to cover home health services and private

duty nursing services. In response to the high costs of nursing facility care, combined with criticism of Med-

icaid’s institutional bias, states and the Federal government began to look for ways to provide long-term care

in less restrictive, more cost-eective ways. In 1970, home health services for those entitled to nursing home

care became mandatory. Since that date, Medicaid has evolved into a program that allows states considerable

exibility to cover virtually all long-term care services and supports that people with disabilities need to live

22 Understanding Medicaid Home and Community Services: A Primer

independently in their homes and in a wide range

of community residential care settings.

The Federal Medicaid statute (Title XIX of the Social

Security Act) generally requires states to specify the

amount, duration, and scope of each service they

provide, which must be sucient to reasonably

achieve its purposes. States may not place limits on

services or arbitrarily deny or reduce coverage of

required services solely because of diagnosis, type

of illness, or condition—called the comparability

requirement.

Generally, a State Plan must be in eect throughout

an entire state (i.e., the amount, duration, and scope

of coverage must be the same statewide—called

the “statewideness” requirement). The Social Se-

curity Act has some exceptions, notably (1)states

operating Section (§)1915(c) home and community-

based services (HCBS) waiver programs (hereafter

called HCBS waiver programs) are permitted to

target services by age and diagnosis and can oer

them on a less than statewide basis, and (2)target-

ed case management services oered as an option-

al benet under the State Plan are not subject to the

statewideness requirement. (§1115 Research and

Demonstration waivers can also operate on a less

than statewide basis.)

By 1999, the year of the Olmstead decision, every

state was providing home and community servi ces

under one or more of the available options except

for §1915(i) (which did not become eective until

2007). By then, Medicaid had become the nation’s

major public nancing program for long-term care

for low-income persons of all ages with all types of

physical and mental disabilities.

3

Since 1988, Medicaid spending for home and com-

munity services has increased dramatically. In that

year, expenditures for all long-term care services

totaled $23 billion. Nearly 90 percent of those dol-

lars paid for institutional services in nursing facilities

and intermediate care facilities for persons with in-

tellectual disabilities (ICFs/ID). Only 10 percent was

spent on home and community services (i.e., HCBS

waivers, personal care, home health, and targeted

case management).

4

In 2008, total Medicaid spending for all long-term

care services had increased to $106.4 billion. Insti-

tutional spending had dropped to 57.3 percent and

HCBS spending increased to 42.7 percent. The latter

percentage, however, masks large variations among

states in the share of spending devoted to home

and community services and among dierent popu-

lations. For example, in 2008 only 10 states spent

50 percent or more of their long-term care budgets

on home and community services. New Mexico and

Oregon ranked at the top with over 70 percent; Mis-

sissippi was at the bottom with 13.9 percent.

5

Expansion of home and community services relative

to institutional services has been particularly pro-

nounced for individuals with intellectual disabilities

and other developmental disabilities (ID/DD, hereaf-

ter called developmental disabilities). In 2008, only

four states (New Mexico, Washington, Oregon, and

California) spent more than 50 percent of their Med-

icaid long-term care budgets on home and commu-

nity services for the aged and disabled population,

while 42 states spent at least half of their Medicaid

long-term care budgets on home and community

services for individuals with developmental disabili-

ties. As an example, Oregon’s spending on home

and community services for the ID/DD population

was 100 percent compared with 53.6 percent for the

aged and disabled population.

Nationally, in 2008, 35.5 percent of Medicaid’s total

long-term care expenditures for persons with devel-

opmental disabilities were allocated to institutional

services and 64.5 percent to home and community

services. The allocation for elderly persons and

younger persons with physical disabilities was the

opposite—68.4 percent of total long-term care

expenditures for institutional services and 31.6 per-

cent for home and community services.

6

23

Chapter 1: Medicaid Coverage of Home and Community Services: Overview

Major Features of Medicaid’s Provisions

for Home and Community Services

The remainder of this chapter presents a brief over-

view of the Medicaid law, regulations, and policies

that give states the exibility to create comprehen-

sive home and community service systems for peo-

ple of all ages with all types of physical and mental

impairments and/or chronic health conditions. To

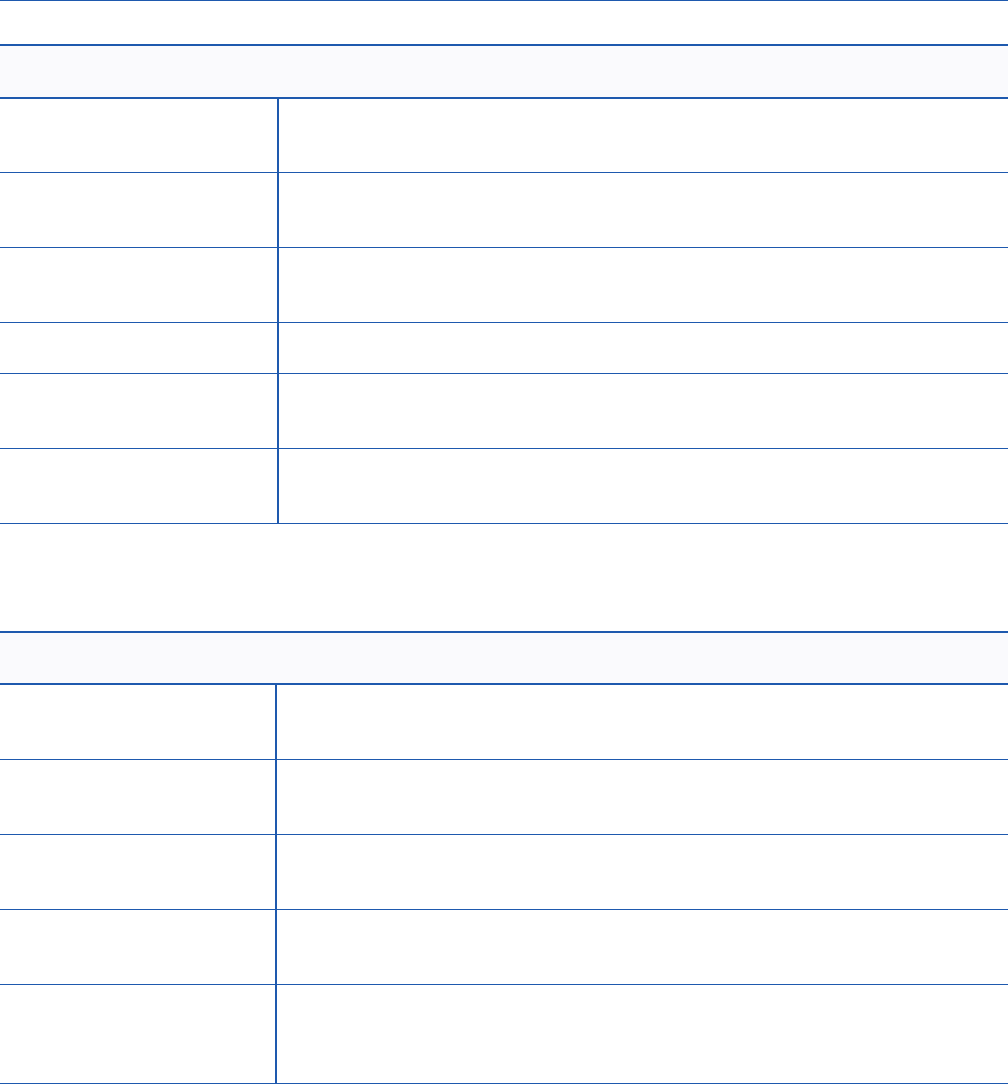

provide context for the discussion, Table 1-1 lists

the major relevant provisions of Medicaid law. This

chronological summary illustrates the historical

expansion of Medicaid long-term care services away

from a primary focus on institutional care.

Key benets for providing home and community

services include both mandatory services such as

Home Health and optional services such as Personal

Care and Rehabilitation. Additional Medicaid provi-

sions, such as the HCBS waiver authority, enable

states to oer a comprehensive range of home and

community services.

Mandatory State Plan Services:

Home Health

Since 1970, services under the Home Health benet

have been mandatory for people entitled to nursing

facility care.

7

States are mandated to cover nursing

home care for categorically eligible persons age 21

or older. This mandate entitles persons age 21 or

older to nursing facility care. States have the op-

tion to cover nursing home care for other Medicaid

beneciaries as well, such as persons under age 21.

If a state chooses to cover persons under age 21,

they would also be entitled to nursing home care.

However, being entitled to nursing home care does

not mean that one is eligible for nursing home care.

In order to receive Medicaid-covered nursing home

care, entitled persons must also meet nursing home

eligibility criteria—called level-of-care criteria.

8

(See

Chapter 3 for additional information about eligibil-

ity for services under the Home Health benet.)

Federal regulations require that Home Health ser-

vices include nursing, home health aides, medical

supplies, medical equipment, and appliances suit-

able for use in the home. States have the option of

providing additional therapeutic services under the

Home Health benet—including physical therapy,

occupational therapy, and speech pathology and

audiology services.

9

States may establish reasonable

standards for determining the extent of such cover-

age using criteria based on medical necessity or

utilization control.

10

In doing so, a state must ensure

that the amount, duration, and scope of coverage

are reasonably sucient to achieve the purpose

of the service.

11

All Home Health services must be

medically necessary and authorized by a physician’s

order as part of a written plan of care.

In 1998, following the ruling of the U.S. Court of

Appeals for the Second Circuit in DeSario v. Thomas,

CMS sent a letter to State Medicaid Directors clarify-

ing that states may develop a list of pre-approved

items of medical equipment as an administrative

convenience but must provide a reasonable and

meaningful procedure for beneciaries to request

items that do not appear on such a list.

12

Home

Health services are dened in Federal regulation

as services provided at an individual’s place of

residence. In 1997, however, the Federal Court of

Appeals for the Second Circuit ruled in Skubel v.

Fuoroli that home health nursing services may be

provided outside the home, as long as they do not

exceed the hours of nursing care that would have

been provided in the home.

13

(See Chapter 3 for ad-

ditional information on this ruling.)

24 Understanding Medicaid Home and Community Services: A Primer

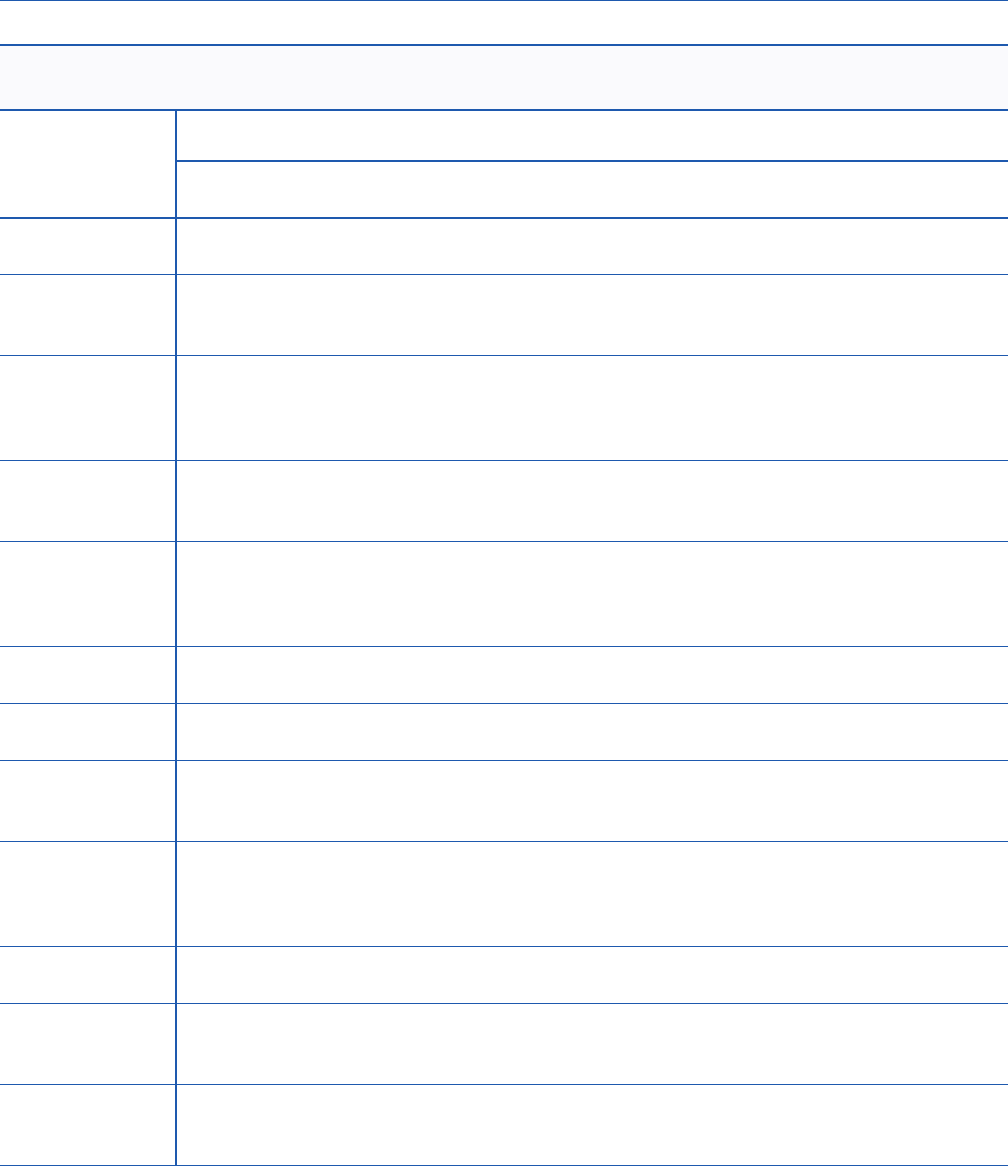

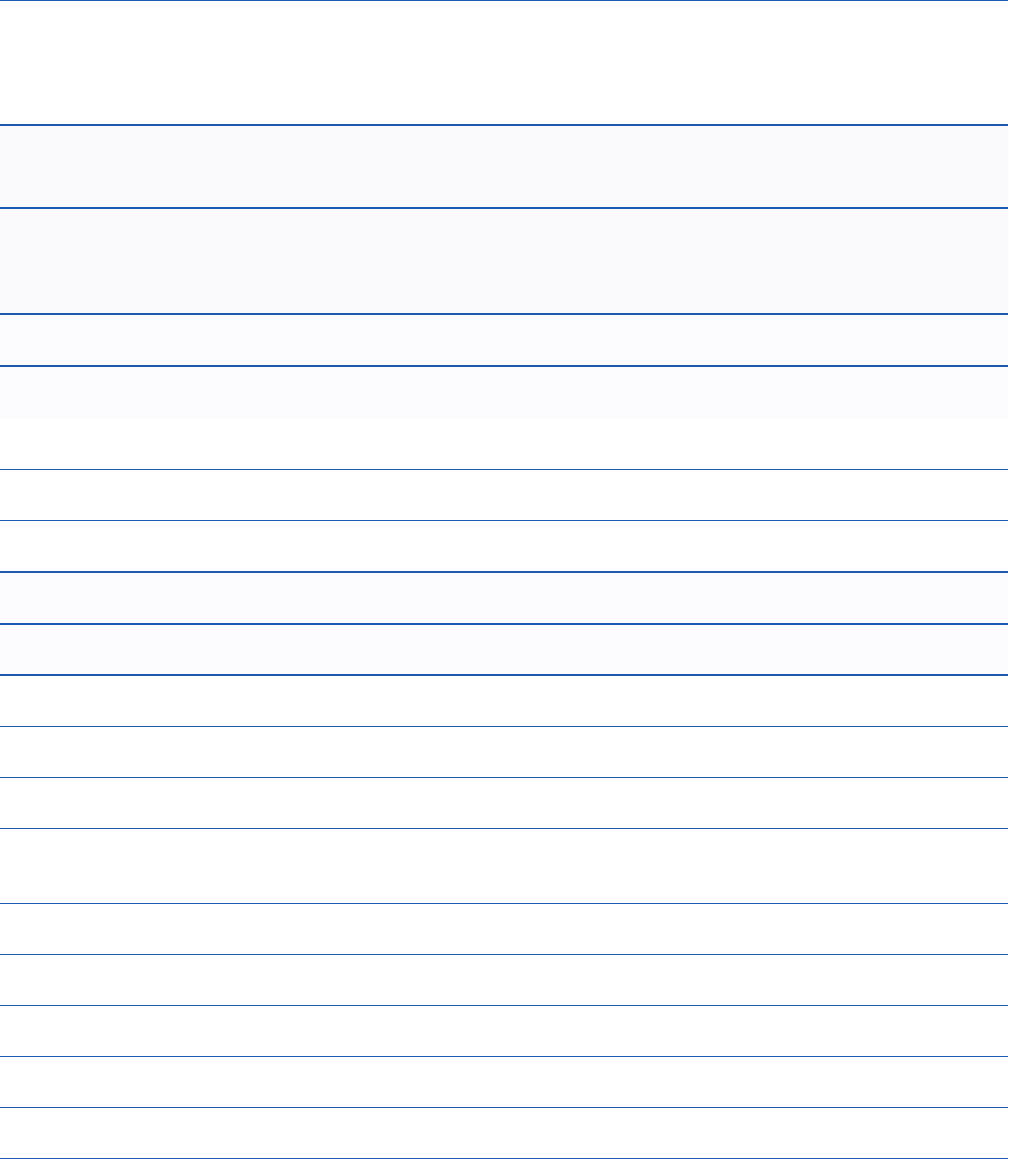

TABLE 1-1 Medicaid’s Legislative Provisions Regarding Long-Term Care Services

1965 Establishment of Medicaid

14

• Mandatory coverage of SNFs for categorically eligible persons age 21 or older.

• Optional coverage of Home Health services and Rehabilitation services.

1967 Early and Periodic Screening, Diagnosis, and Treatment (EPSDT) mandate for children under age 21.

15

States given the option to provide services not covered by their State Plans under EPSDT.

1970 Mandatory coverage of Home Health services for those entitled to SNF services.

1

6

1971 Optional coverage of intermediate care nursing facilities and ICFs/ID.

17

1972 Optional coverage of children under age 21 in psychiatric hospitals.

1

8

1973 Option to allow people receiving supplemental security income (SSI) to return to work and maintain

their Medicaid benets.

1

9

1981 Establishment of HCBS waiver authority.

2

0

1982 Option to allow states to extend Medicaid coverage to certain children with disabilities who live at home

but who, until this 1982 provision, were eligible for Medicaid only if they were in a hospital, nursing facil-

ity, or ICF/ID. Also known as the Katie Beckett or Tax Equity and Fiscal Responsibility Act (TEFRA) provi-

sion.

2

1

1986 Option to cover targeted case management (TCM). States are allowed to cover TCM services without

regard to statewideness and comparability requirements.

22

Option to oer supported employment services through HCBS waiver programs to individuals who had

been institutionalized some time prior to entering the HCBS waiver program.

23

1988 Establishment of special nancial eligibility rules for institutionalized persons whose spouse remains in

the community, to prevent spousal impoverishment.

2

4

1989 EPSDT mandate amended to require states to cover any service a child needs, even if it is not covered

under the State Plan.

25

1993/94 Removal of requirements for physician authorization and nurse supervision for personal care services

provided under the State Plan. States explicitly authorized to provide personal care services outside the

individual’s home.

26

Personal Care added to the statutory list of Medicaid services. (Personal Care was an

option since the mid-1970s, when it was established administratively under the Secretary of Health and

Human Services’ authority.)

1997 Removal, under the Balanced Budget Act of 1997, of the “prior institutionalization” test as a requirement

for receiving supported employment services through an HCBS waiver program. Addition of rst oppor-

tunity for states to create a Medicaid “buy-in” for people with disabilities. Establishment of the Program

of All Inclusive Care for the Elderly (PACE) as a State Plan option.

1999 Additional options under the Ticket to Work and Work Incentives Act for states to create a buy-in pro-

gram for people with disabilities and to remove employment barriers.

27

2005 Establishment of a new Medicaid State Plan authority for providing HCBS under §1915(i) of the Social

Security Act, under the Decit Reduction Act of 2005 (DRA-2005), eective 2007. The DRA-2005 also

expands options for Medicaid participants to direct their services under HCBS waivers and State Plan

Personal Care programs, through §1915(j) of the Social Security Act.

2010 Establishment, under the Aordable Care Act of 2010, of a new authority under §1915(k) of the Social

Security Act, eective October 2011. This authority allows states to provide “Community-based Atten-

dant Services and Supports” under the Community First Choice Option.

25

Chapter 1: Medicaid Coverage of Home and Community Services: Overview

Mandatory State Plan Services: EPSDT

The Federally mandated Early and Periodic Screen-

ing, Diagnosis, and Treatment (EPSDT) program for

children from birth until they turn age 21 entitles

Medicaid-eligible children to services found nec-

essary to diagnose, treat, or ameliorate a defect,

physical or mental illness, or a condition identied

by an EPSDT screen. The original 1967 legislation

gave states the option to cover treatment services

not covered under the Medicaid State Plan. In

1989, Congress strengthened the EPSDT mandate

by requiring states to cover all treatment services

dened under §1905(a), regardless of whether or

not those services are covered in their Medicaid

State Plan.

28

As a result, EPSDT programs now cover

the broadest possible array of Medicaid services,

including personal care and other services provided

in the home.

Optional State Plan Services:

Personal Care

Since the mid-1970s, states have had the option

to oer personal care services under the Medicaid

State Plan. This option was rst established adminis-

tratively under the Secretary’s authority to add cov-

erages over and above those spelled out in §1905

of the Social Security Act, if such services would

further the Social Security Act’s purposes. In 1993,

Congress took the formal step of adding personal

care to the list of services spelled out in the Medic-

aid statute.

29

(See Chapter 4 for more information

about the State Plan Personal Care benet.)

When the Personal Care benet option was created,

it had a decidedly medical orientation. The services

had to be prescribed by a physician, supervised by a

registered nurse, and delivered in accordance with

a service plan. Moreover, they could be provided

only in a person’s place of residence. Generally, the

personal care services a state oered were for assist-

ing individuals to perform activities of daily living

(ADLs)—bathing, dressing, eating, toileting, and

transferring (e.g., from a bed to a chair). Personal

care workers could provide other forms of assis-

tance (e.g., housekeeping and laundry) only on a

limited basis and only if they were incidental to the

delivery of personal care services.

Starting in the late 1980s, some states sought to

broaden the scope of personal care services and

provide them outside the individual’s home in order

to enable beneciaries to participate in community

activities. In 1993, when Congress formally incor-

porated personal care into Federal Medicaid law, it

gave states explicit authorization to provide per-

sonal care outside an individual’s home.

30

Congress

went even a step further in 1994, allowing states

to (1)use means other than nurse supervision to

oversee the provision of personal care services, and

(2)establish means other than physician prescrip-

tion for authorizing such services. In November

1997, CMS issued new regulations concerning

optional Medicaid State Plan personal care services

to reect these statutory changes.

31

In January 1999, CMS released a State Medicaid

Manual Transmittal that thoroughly revised and

updated guidelines concerning coverage of per-

sonal care services. (See the Resources section of

this chapter for web links to the Medicaid Manual.)

New Manual materials make clear that personal care

services may include assistance not only with ADLs

but also with instrumental activities of daily living

(IADLs), such as personal hygiene, light housework,

laundry, meal preparation, transportation, grocery

shopping, using the telephone, medication man-

agement, and money management. Additionally,

the guidelines claried that all relatives except

“legally responsible relatives” (i.e., spouses, and par-

ents of minor children) could be paid for providing

personal care services to beneciaries.

The Manual further claried that, for persons with

cognitive impairments, personal care may include

“cueing along with supervision to ensure the indi-

vidual performs the task properly.” It also explicitly

recognized that the provision of personal care ser-

vices may be directed by the people receiving them.

Direction by participants includes training and

supervising personal care attendants. The ability of

participants to direct their personal care services

has been a feature of many personal assistance

programs for many years (both under Medicaid and

in programs funded only with state dollars). For ex-

ample, participant direction was built into the Mas-

sachusetts Medicaid Personal Care program from its

inception. Taken together, these ground-breaking

26 Understanding Medicaid Home and Community Services: A Primer

changes in Federal policy can help pave the way

for a state to broaden coverage of these services. In

order to take advantage of these changes, a state

must amend its State Plan. Neither the statutory

provisions nor the revised Federal regulations and

State Medicaid Manual guidelines dictate that a

state must change the scope of its pre-1993 per-

sonal care coverage.

In 2005, 36 states covered personal care services

under their Medicaid State Plans.

32

The most likely

explanation for this less than national coverage is

that some states have elected to cover personal

care services through more exible and easy to

target HCBS waiver programs instead of adding the

benet to their State Plan. (See Chapter 4 for a dis-

cussion of the various options for covering personal

care, including their advantages and drawbacks.)

The §1915(j) Authority. The DRA-2005 added

§1915(j) to the Social Security Act, eective January

2007.

33

This authority permits a state to institute an

option for participants to have individual budgets

to purchase non-traditional goods and services

other than personal care to the extent that expendi-

tures would otherwise be made for human assis-

tance. It also allows states the option to disburse

cash prospectively to participants who direct their

services under the State Plan Personal Care benet

or an HCBS waiver program. Participants may also

determine rates of pay for their workers, accumulate

funds earmarked for the purchase of a specic item

designed to increase independence or substitute for

human assistance, and work with a scal intermedi-

ary to perform payroll and tax functions—called the

“budget authority.” Absent the §1915(j) authority,

participant direction of Medicaid State Plan per-

sonal care services is limited to hiring, supervising,

and dismissing (if needed) their workers—called the

“employer authority.”

States may use the §1915(j) authority only in pro-

grams already oered under its Medicaid State Plan

or an HCBS waiver (i.e., states may not oer the spe-

cic participant-directed services options under the

§1915(j) authority except in an existing State Plan

Personal Care program or HCBS waiver program).

(See Chapter 7 for a detailed description of this new

authority and a discussion of participant-directed

service options—also called self- or consumer-di-

rected—that can be oered under several Medicaid

authorities.)

Optional State Plan Services:

Targeted Case Management

Until 1986, the only practical avenue available for a

state to secure Medicaid funding for free standing

case management services (i.e., case management

services not delivered as part of some other service

or conducted in conjunction with the state’s opera-

tion of its Medicaid program) was through an HCBS

waiver program. Coverage of case management ser-

vices in HCBS waiver programs was nearly universal

at that time.

In 1986, Congress created an option for states to

cover what were termed “targeted case manage-

ment” services under their State Plan.

34

The ex-

pressed statutory purpose of targeted case man-

agement is to assist Medicaid recipients in “gaining

access to needed medical, social, educational, and

other services.” This optional benet is exempt from

the comparability requirement to make services

available to all recipients. A state is permitted to

amend its State Plan to cover case management

services for one or more specied groups of Medic-

aid recipients (hence the term targeted). It may also

oer these services on a less-than-statewide basis

(through a State Plan amendment instead of secur-

ing a waiver).

35

Given the expressed statutory purpose of the ben-

et—to assist individuals to obtain services from a

wide variety of public and private programs—the

scope of services a state may furnish through the

targeted case management option is relatively

broad. In addition to assessment and service/

support planning, referrals, and monitoring the

delivery of services and supports to ensure they are

meeting a beneciary’s needs, covered activities

include assistance in obtaining food stamps, emer-

gency housing, or legal services. (See Chapter 4 for

more information about this benet.)

27

Chapter 1: Medicaid Coverage of Home and Community Services: Overview

Optional State Plan Home and

Community-Based Services

36

The DRA-2005 added §1915(i) to the Social Security

Act, which was amended by the Patient Responsibil-

ity and Aordable Care Act of 2010. The §1915(i) au-

thority gives states the option to oer a wide range

of home and community-based services without

having to secure Federal approval of a waiver. The

§1915(i) authority provides states an opportunity to

oer services and supports before individuals need

institutional care, and also provides a mechanism to

provide State Plan HCBS to individuals with mental

health and substance use disorders.

Unlike other State Plan services, under §1915(i),

states may design service packages without regard

to comparability.

37

States may oer HCBS to specic,

targeted populations and oer servi ces that dier in

amount, duration, and scope to specic population

groups, including eligibility groups as authorized

under §1915(i)(6)(c), either through one or multiple

§1915(i) service packages. Services must be avail-

able statewide.

Optional State Plan Services:

Community Choice Option

38

The Aordable Care Act added §1915(k) to the

Social Security Act, eective October 2011, which

allows states to provide “Community-based At-

tendant Services and Supports”—called the Com-

munity First Choice Option. Under §1915(k), states

that provide home and commu nity-based atten-

dant services and supports through their State

Plans under this option will receive a six percentage

points higher Federal match. Individuals must be

eligible for Medicaid under the State Plan and have

an income that does not exceed 150 percent of the

Federal Poverty Level, or, if their income is greater,

they must meet institutional level-of-care criteria.

CMS plans to issue a Notice of Proposed Rule Mak-

ing related to this provision of the Aordable Care

Act in early 2011.

Other Optional State

Plan Home and Community Services

When Medicaid was enacted, states were given the

option of covering a wide range of services, several

of which can be provided in home and/or commu-

nity settings. They include rehabilitation services,

private duty nursing, physical and occupational

therapy, and transportation services. In 2000, every

state provided at least one optional service.

The Rehabilitation option, in particular, oers states

the means to provide a range of supportive services

to people in home and community settings. Med-

icaid denes rehabilitation services as any medical

or remedial services recommended by a physician

or other licensed practitioner of the healing arts for

maximum reduction of physical or mental disabil-

ity, and restoration of a recipient to his or her best

possible functional level.

39

Rehabilitation services

can be provided to people with either physical or

mental disabilities.

The Rehabilitation option is a very exible benet,

because services may be furnished either in the

person’s residence or elsewhere in the commu-

nity. Many states cover psychosocial rehabilitation

services, which—when combined with personal

care and targeted case management servi ces—can

meet a wide range of service and support needs for

persons who have a serious mental illness. In 2005,

46 states used the Rehabilitation option to provide

services for persons with a serious mental illness;

33 states used the Rehabilitation option to provide

other services.

40

28 Understanding Medicaid Home and Community Services: A Primer

Optional Institutional Services

The 1971 addition of the option to cover ser-

vices provided by intermediate care nursing

facilities, called intermediate care facilities (ICFs),

and ICFs/ID, moved the Medicaid program into

nancing additional nursing home care and

institutional services for the ID/DD population.

States adding optional institutional coverage of

ICFs/ID could receive Federal matching funds to

help nance services for persons with develop-

mental disabilities, which had previously been

supportable only with state funds.

Likewise, states adding optional coverage of

ICFs could receive Federal matching funds to

help nance a non-skilled level of nursing care

(which had previously been supportable only

with state funds). Over the next few years, every

state and the District of Columbia chose to cover

ICFs and ICFs/ID in their State Plan.

The option to cover nursing ICFs and ICF/IDs as-

sumed greater importance after 1981, when the

waiver authority was created. This was because

§1915(c) waiver services can be provided only

insofar as they provide an alternative to institu-

tional care.

41

(In 1987, Congress abolished the

distinction between SNFs and ICFs. Nursing fa-

cilities were mandated to provide both a skilled

and intermediate level of care.)

The Rehabilitation option is not generally used

to furnish long-term care to individuals with dis-

abilities or chronic health conditions other than

mental illness. During the 1970s and 1980s, a few

states secured approval to cover daytime services

for persons with developmental disabilities under

either the Clinic or the Rehabilitation option. How-

ever, CMS ultimately ruled that the services being

furnished were habilitative rather than rehabilita-

tive and consequently could not be covered under

either option by additional states. The main basis for

the ruling was that habilitative services could only

be furnished to residents of ICFs/ID under the Med-

icaid State Plan or through an HCBS waiver program

for individuals otherwise eligible for ICF/ID services.

States with existing programs serving individuals

with intellectual disabilities and other develop-

mental disabilities were grandfathered under the

Omnibus Reconciliation Act (OBRA) of 1989.

A few states have maintained their State Plan cover-

age of these services; others have terminated them

in favor of oering similar services through an HCBS

waiver program.

42

With the creation of the new

HCBS State Plan option under the §1915(i) author-

ity, states may now cover habilitation as a home and

community-based service under the State Plan.

The HCBS Waiver Authority

In 1981, Congress authorized the waiver of certain

Federal requirements to enable states to provide

home and community services (but not room and

board) to individuals who would otherwise require

institutional services reimbursable by Medicaid (i.e.,

services in a skilled nursing facility, an intermedi-

ate care nursing facility, or an ICF/ID). The waiver

programs are often called §1915(c) waivers (named

after the section of the Social Security Act that

authorized them), but are also called HCBS waivers,

the term used in this Primer.

43

Under the §1915(c) waiver authority, states can

provide services not usually covered by the

Medicaid program, as long as these services are

required to prevent institutionalization. Services

covered under waiver programs include case man-

agement, homemaker, home health aide, personal

care, adult day health, habilitation, respite care, and

“such other services requested by the state as the

Secretary of Health and Human Services (HHS) may

approve.” Services for individuals with a chronic

mental illness were added in the late 1980s: “day

treatment or other partial hospitalization services,

psychosocial rehabilitation services, and clinic ser-

vices (whether or not furnished in a facility).”

Neither the statute itself nor CMS regulations

further specify or dene the scope of the listed

services. However, the law that created the waiver

program expressly permits the Secretary of HHS to

approve services beyond those specically spelled

out in the law, as long as they are necessary to avoid

institutionalization and are cost-eective. In the

29 years since the waiver author ity became avail-

able, CMS has approved a wide range of additional

services.

29

Chapter 1: Medicaid Coverage of Home and Community Services: Overview

In the early 1990s, CMS rst issued a standard HCBS

waiver application format for states to submit

requests to operate an HCBS waiver program. The

standard format included denitions of services

states commonly cover in their HCBS waiver pro-

grams. The services listed in the standard format ap-

pear there because they are included in the listing

contained in the statute, or are additional services

that states frequently oer.

In 2005, CMS extensively modied its standard

§1915(c) application to obtain greater detail about

how the proposed program would operate. States

must now provide specic information about how

their programs comply with Federal standards, as

well as detailed information about their quality im-

provement systems. Beginning in 2006, CMS began

oering a web-based version of the application. The

conversion to a web-based application streamlines

the preparation of waiver applications and amend-

ments, and improves communication between

states and CMS about waiver requests.

The Waiver Application Instructions represent the

most current guidance related to HCBS waivers. The

instructions provide CMS-suggested denitions

of services that states may cover under their HCBS

waiver programs—identied as Core Service Deni-

tions. The services a state may oer are by no means

limited to those that appear in the standard format,

nor are the proposed denitions required. (See the

Resources section of this chapter for a link to all ap-

proved HCBS waivers and a link to the online waiver

application and technical guidance document.)

During Federal scal year (FFY) 2008, 48 states and

the District of Columbia operated 314 HCBS waiver

programs. This number includes waivers that CMS

had approved but that had not yet been imple-

mented as of September 30, 2008. The two states

that did not have HCBS waivers—Arizona and Ver-

mont—provided similar services as part of Research

and Demonstration waivers authorized by §1115 of

the Social Security Act.

44

Expenditures for waiver services totaled $30 bil-

lion in 2008 and roughly three-fourths was used to

purchase services and supports for persons with

developmental disabilities, including persons with

autism spectrum disorders or intellectual disabili-

ties.

45

Almost all other waiver expenditures in the

same year were for older adults and younger adults

with physical disabilities; a few smaller population

groups accounted for the remaining waiver expen-

ditures.

46

The Katie Beckett Provision

The Katie Beckett provision is in a statute—the

Tax Equity and Fiscal Responsibility Act 134—and

was added to Medicaid in 1982. Katie Beckett is

the name of the child whose parents petitioned

the Federal Government for her to receive Medic-

aid services at home instead of in a hospi tal, and

whose plight led the Reagan Administration to urge

Congress to enact the provision. Prior to enactment,

if a child with disabilities lived at home, the parents’

income and resources were automatically counted

(deemed) as available for medical expenses. How-

ever, if the same child was institutionalized for 30

days or more, only the child’s own income and re-

sources were count ed in the deeming calculation—

substantially increasing the likelihood that a child

could qualify for Medicaid. This sharp divergence in

methods of counting income often forced families

to institutionalize their children simply to obtain

medical care for them.

TEFRA 134 amended the Medicaid statute to give

states the option to waive the deeming (i.e., count-

ing) of parental income and resources for children

under 18 years old who were living at home but

would otherwise be eligible for Medi caid-funded

institutional care. Not counting parental income en-

ables these children to receive Medicaid services at

home or in other community settings. Many states

use this option, which requires them to determine

that (1)the child needs the level of care provided

in an institution, (2)it is appropriate to provide care

outside a facility, and (3)the cost of care at home is

no more than the cost of institutional care. In states

that use this option, parents may choose either

institutional or community care for their Medicaid-

eligible children.

30 Understanding Medicaid Home and Community Services: A Primer

The Program of All-Inclusive Care

for the Elderly (PACE)

The Program of All-Inclusive Care for the Elderly—

authorized by the Balanced Budget Act of 1997

(BBA-97)—is a capitated program that features a

comprehensive service delivery system that in-

tegrates Medicare and Medicaid nancing. The

BBA-97 established the PACE model of care as a

permanent method for organizing service delivery

within the Medicare program, and enables states

to provide PACE services to Medicaid beneciaries.

Participants must be at least 55 years old, eligible

for Medicare or Medicaid or both, and certied as

meeting a state’s nursing home level-of-care criteria.

For most participants, the comprehensive service

package permits them to continue living at home

rather than be admitted to an institution.

In 2009, 72 PACE programs were operating in 30

states. The State Plan must include PACE as a Med-

icaid benet before the state and the Secretary of

HHS can enter into program agreements with PACE

providers. Participants must be at least 55 years old,

live in the PACE service area, and be certied as eli-

gible for nursing home care by the appropriate state

agency. The PACE program becomes the sole source

of services for persons dually eligible for Medicare

and Medicaid who choose to enroll.

An interdisciplinary team, consisting of professional

and paraprofessional sta, assesses participants’

needs, develops service plans, and delivers all

services (including primary and acute health care

services, home and community services, and when

necessary, nursing facility services). Financing for

these services is integrated to promote a seamless

system of care. PACE programs provide social and

medical services primarily in an adult day health

center, supplemented by in-home and other ser-

vices in accordance with participants’ needs. The

PACE service package must include all Medicare

and Medicaid covered services, and other services

determined necessary by the interdisciplinary team

for the care of the PACE participant. (See Chapter 8

for more information about the PACE program and

other Medicaid managed care options.)

This brief overview of Medicaid’s statutory, regula-

tory, and other policy provisions related to home

and community services provides a context for

more detailed discussions in the chapters to come.

Some of the institutional bias that remains in the

program can be changed only by Congressional

amendment of Medicaid law (e.g., changing home

and community-based services from an optional to

a mandatory benet). But numerous provisions give

state policymakers considerable freedom in design-

ing their home and community service system to t

their state’s particular needs. They have the option,

in particular, to eliminate use of more restrictive

nancial criteria for waiver services than for institu-

tional care. They also have considerable exibility to

create consumer-responsive systems that facilitate

home and community living.

In the next several decades, as already noted, the

U.S. population will age dramatically. Even if dis-

ability rates among older persons decline, more

people will need long-term care services than at any

other time in our nation’s history. Institutional care

is costly. Given the projected demand for long-term

care, it is advisable for states to continue working

to create comprehensive long-term care service

systems that will enable people with disabilities

and/or chronic health conditions—whatever their

age or the severity of their condition—to live in

their homes and community settings rather than in

institutions.

The Medicaid program can be the centerpiece of

such a system—allowing states numerous options

to provide home and community services that

keep costs under control at the same time that they

enable people of all ages with disabilities and/or

chronic health conditions to retain their indepen-

dence and dignity.

31

Chapter 1: Medicaid Coverage of Home and Community Services: Overview

Resources

Since the Primer was rst published in 2000, numerous reports and other resources have become available

on the Internet. This section includes key publications and Internet resources regarding Medicaid long-

term care generally and home and community services specically. Most of the publications cite addition-

al resources, and the websites also have links to other sources of information.

Publications

Houser, A., Fox-Grage, W., and Gibson, M. (2009). Across the States 2009:

Proles of Long-Term Care and Independent Living. Washington, DC: AARP Public Policy Institute.

This report is the eighth edition of the AARP Public Policy Institute’s state long-term care reference report.

Published approximately every 2 years, the Across the States series was developed to help inform policy dis-

cussions among public and private sector leaders in long-term care throughout the United States. Across the

States 2009 presents comparable state-level and national data for more than 140 indicators, drawn together

from a wide variety of sources into a single convenient reference. This publication presents the most up-to-

date data available at the time of production, and is displayed in easy-to-use maps, graphics, tables, and state

proles.

Available at http://www.hcbs.org/moreInfo.php/doc/2536

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. (2008). Application for a §1915(c) Home and Community-Based

Waiver [Version 3.5]: Instructions, Technical Guide and Review Criteria. Baltimore, MD: USDHHS.

This publication contains extensive information concerning Federal policies that apply to the operation of an

HCBS waiver as well as technical guidance for completing the application.

Available at https://www.hcbswaivers.net/CMS/faces/portal.jsp under links and downloads, entitled §1915(c)

Waiver Application and Accompanying Materials.

CMS State Medicaid Director Letter (November 19, 2009). Implementation of §6087 of the Decit Reduction

Act of 2005 Regarding §1915(j) of the Social Security Act.

This letter provides guidance on the implementation of §6087 of the Decit Reduction Act of 2005, Public

Law Number 109-171. Section 6087, the “Optional Choice of Self-Directed Personal Assistance Services (Cash

32 Understanding Medicaid Home and Community Services: A Primer

and Counseling),” amended §1915 of the Social Security Act by adding a new subsection (j). The guidance also

applies to §1915(c) HCBS waiver programs when states oer a self-direction option and permit participants to

purchase “individual directed goods and services.” The letter oers information on (1)Background, (2)Medic-

aid Authorities, (3)Criteria, (4)Support and Monitoring, and (5)Compliance with the Guidance.

Available at http://www.cms.hhs.gov/SMDL/SMD/ItemDetail.asp?ItemID=CMS1230894

The Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured. (2009). Medicaid Home and Community-Based Ser-

vice Programs: Data Update. Washington, DC: Kaiser Family Foundation.

This report presents a summary of the main trends to emerge from an analysis of the 2006 expenditures and