RESEARCH BRIEF | 1

August 2022 (REVISED)

ASPE RESEARCH BRIEF

HHS OFFICE OF THE ASSISTANT SECRETARY FOR PLANNING AND EVALUATION

OFFICE OF BEHAVIORAL HEALTH, DISABILITY, AND AGING POLICY

LONG-TERM SERVICES AND SUPPORTS FOR

OLDER AMERICANS: RISKS AND FINANCING, 2022

Most Americans underestimate the risk of developing a disability and needing long-term

services and supports (LTSS). Using microsimulation modeling, we estimate that over half

(56%) of Americans turning 65 today will develop a disability serious enough to require LTSS,

although many will need assistance for less than three years. About one in five of all adults

(22%), however, will have a disability for more than five years. On average, an American

turning 65 today will incur $120,900 in future LTSS costs, measured in today’s dollars.

Families will pay more than one-third (37%) of the costs themselves out of pocket, with the

rest covered by public programs and private insurance. Although most people with LTSS

needs will spend relatively little on their care, 14% will spend at least $100,000 out of pocket

for future LTSS. But these paid services do not cover all care people need, and consistent

with prior research we find that family caregivers provide substantial unpaid care. Valuing

unpaid care contributions at the wage of a paid caregiver, we estimate that unpaid family care

for older adults with significant disabilities who receive care is worth $204,000 on average,

more than the expected cost of all paid LTSS. Without help from unpaid family caregivers,

families and public programs would spend much more on LTSS.

Background

Long-term services and supports (LTSS) includes a range of assistance individuals may

need to meet their health or personal needs over an extended period.

1

Most LTSS is

not medical care, but rather assistance with the basic personal tasks of everyday life,

sometimes called activities of daily living (ADLs), which include such tasks as bathing,

dressing, toileting and eating (Katz et al. 1963).

2

Many Americans prefer not to think

about this need for assistance or who will provide it. They underestimate the likelihood

that they will need help and how much it will cost (Wiener et al. 2015; Kane 2013;

Tompson et al. 2013). Even if they recognize the possibility of developing a disability

and needing daily help, many Americans mistakenly assume that insurance will cover

these costs. However, health insurance does not cover LTSS costs, and Medicare, the

major public insurance program for older Americans, does not cover most LTSS

expenses (Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services 2015).

3

Relatively few financing options exist for LTSS. Although Medicaid provides LTSS to

those with chronic disabling conditions (Komisar 2013; Tompson et al. 2013),

4

it is

available only for individuals who meet income and other eligibility requirements (U.S.

Department of Health and Human Services 2015). A private market for LTSS insurance

RESEARCH BRIEF | 2

exists, but less than 8% of Americans have purchased coverage (Freundlich 2014),

partly because of high and rising premiums and the exit of insurers from the market

(Scism 2015). Sales figures from recent years suggest the market has stagnated or

even shrunk (Cohen 2016; Schmitz and Giese 2019; Ujvari 2018). In 2018, just

276,000 people received benefits from long-term care insurance (LTCI) and about 6.58

million people--less than 6% of the population ages 50 and older--had a long-term care

policy (National Association of Insurance Commissioners 2019). For some older adults,

the costs of LTSS are likely to outstrip retirement savings. Researchers at the

Employee Benefit Research Institute found that accounting for LTSS expenses

significantly increase the number of retirees projected to have inadequate resources to

cover living expenses (VanDerhei 2015).

As the United States population ages, a growing number of older adults will likely need

and use LTSS. Most Americans who receive paid LTSS pay some share out of pocket.

Those with longer spells may pay out of pocket until they qualify for Medicaid. Reliance

on Medicaid for those who cannot afford the full cost of LTSS may increase federal and

state spending for LTSS. The Congressional Budget Office projects that if the share of

adults ages 65 and older with functional limitations remains constant LTSS expenses

(including all paid care financed by Medicaid and other private and public sources,

including Medicare payments for post-acute services) could more than double between

2010 and 2050 as the population grows, increasing from 1.3% to 3.0% of gross

domestic product (Hagen 2013).

To provide context for policymakers and others considering LTSS financing proposals,

this brief presents information about the risk of needing care and associated costs,

based on results from a microsimulation model. This model projects the percentage of

older adults who will develop a disability and use paid LTSS. For those who use paid

LTSS, the model projects how much they will use and for how long. The model also

estimates care costs and how they would be financed under current policies.

Microsimulation modeling describes the average likelihood of these outcomes, as well

as the distribution of these needs and costs. Throughout this brief we focus on

significant disabilities that result in LTSS needs at the threshold for benefits under a tax-

qualified LTCI policy, set in the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act

(HIPAA): a need for assistance with at least two ADLs

5

that is expected to last at least

90 days or a need for substantial supervision for health and safety threats due to severe

cognitive impairment.

6

HIPAA does not count ADL limitations that can be resolved with

special equipment, such as wheelchairs, walkers, handrails, ramps, catheters, and

related devices (Stallard 2011). Estimates of disability prevalence are higher when we

include people with less severe disabilities and people with disabilities that can be

mitigated with special equipment.

Methods

The findings in this brief--an update of Favreault and Dey (2016)--are derived from

analyses using the Urban Institute’s Dynamic Simulation of Income Model 4

(DYNASIM4), a microsimulation model designed to analyze retirement and aging

issues. Starting with a representative sample of individuals and families, the model

RESEARCH BRIEF | 3

“ages” cohorts year-by-year, simulating such demographic events as births, deaths,

marriages, and divorces, and such economic and health events as labor force

participation, earnings, hours of work, disability onset and recovery, retirement, and use

and costs of LTSS. Simulations of these events and outcomes vary with demographic

and other characteristics of the population.

7

As the model ages the population, it

calibrates many key demographic and economic outcomes to the intermediate

assumptions of the Social Security and Medicare trustees’ reports (Board of Trustees,

Federal Old-Age and Survivors Insurance and Federal Disability Insurance Trust Funds

2021; Boards of Trustees, Federal Hospital Insurance and Federal Supplementary

Medical Insurance Trust Funds 2019). Data to inform the model are drawn from the

Health and Retirement Study, especially in the areas of health, disability (including

cognitive impairment and limitations in ADLs and instrumental activities of daily living

[IADLs]), LTSS use, and private LTCI coverage.

8

Because we rely on historical data,

the projections do not reflect how the COVID-19 pandemic might shift LTSS use.

Current and past LTSS prices are set equal to average or median prices reported in the

literature by state of residence, setting (home care, residential care, nursing home), and

whether Medicaid is the payer (Fossett and Burke 2010; Genworth 2019; Grabowski et

al. 2004; Hansen Hunter and Company 2018; Mollica 2009; Ng et al. 2014).

9

These

base projections incorporate the full cost of residential care, including room and board in

addition to costs associated with meeting care needs. They also incorporate home care

services that families purchase in private transactions, which are rapidly evolving and

which some other studies undercount (Doty 2017; HomecarePulse 2019; Kim 2022;

Newquist, DeLiema and Wilber 2015). The projections include hospice care, which

Medicare pays, but excludes other Medicare-financed services that are strictly post-

acute (see Box 1). These choices affect payer mix and comparability with other

estimates of LTSS expenses, including Favreault and Dey (2016).

BOX 1: Should We Include Medicare as a Payer for LTSS?

Many adults are confused about whether Medicare covers personal assistance if they develop LTSS

needs (also referred to as long-term care needs).

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services is clear about Medicare policies on its website

(https://www.medicare.gov/coverage/long-term-care), which states the following:

• “Medicare doesn’t cover long-term care (also called custodial care), if that’s the only care you need.

Most nursing home care is custodial care.”

• “You pay 100% for non-covered services, including most long-term care.”

• “Long-term care is a range of services and support for your personal care needs. Most long-term

care isn’t medical care. Instead, most long-term care is help with basic personal tasks of everyday

life, sometimes called activities of daily living.”

Because Medicare does not cover LTSS when it is the only care people need, some analysts exclude

Medicare when describing who pays for LTSS (Hado and Komisar 2019). However, several prominent

government publications describe Medicare as an important LTSS payer (Hagen 2013; Colello 2022) and

include all Medicare services delivered in certain settings as LTSS. They make this choice because

National Health Expenditure Accounts (NHEA) data enable researchers to determine the settings in which

care is delivered, but not to determine whether the care is non-medical, making disaggregation difficult.

In a departure from Favreault and Dey (2016), we follow Hado and Komisar (2019) and do not include in

our projections any incidental care that Medicare finances, with one exception: the projections include the

value of Medicare-financed hospice care if it is provided to people meeting a HIPAA-level-of-need

threshold.

RESEARCH BRIEF | 4

Finally, we value unpaid family care at the approximate cost of hiring someone to

provide care. For each hour of unpaid care provided to a person with significant

disabilities, we assign a value equal to the median hourly wage for home care workers

in the care recipient’s state of residence. This projection is likely a lower bound for the

total value of unpaid family care because our estimates ignore administrative hiring

costs, any nonwage compensation that paid caregivers receive, and the value of care

provided to older adults with less-significant disabilities, which is likely substantial.

Additional details about the model’s assumptions are available in Johnson (2022).

Results

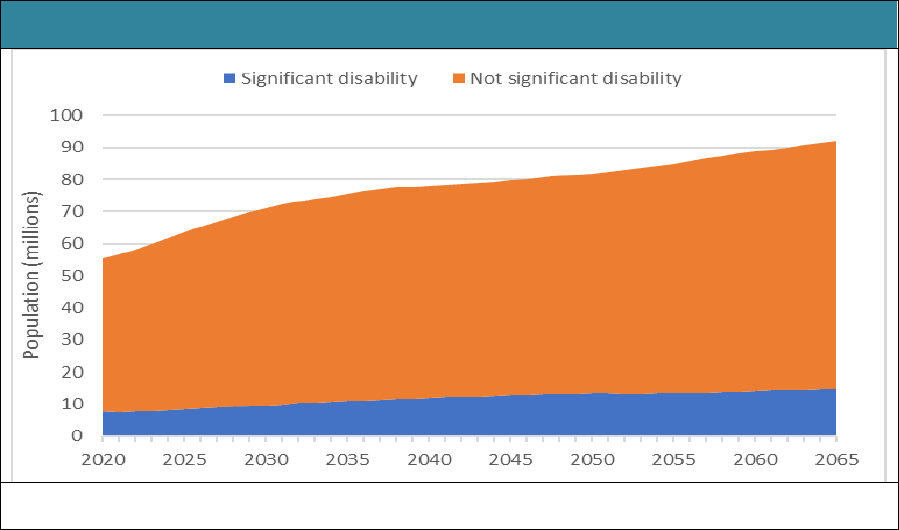

Figure 1 presents projections of the number of people ages 65 and older and the

number with significant disabilities from 2020 to 2065. As expected, given the aging

population, the number with significant disabilities is projected to grow substantially,

increasing from 7.6 million to almost 14.7 million. In percentage terms, the share of the

older population with significant disabilities increases from 14% to 16%.

FIGURE 1. Total Population Ages 65 and Older,

Including the Number of People Projected to Have Significant Disabilities, 2020-2065

SOURCE: Authors’ tabulations from DYNASIM4, run id982.

NOTE: Estimates are for adults born between 1941 and 1974 who survive to age 65.

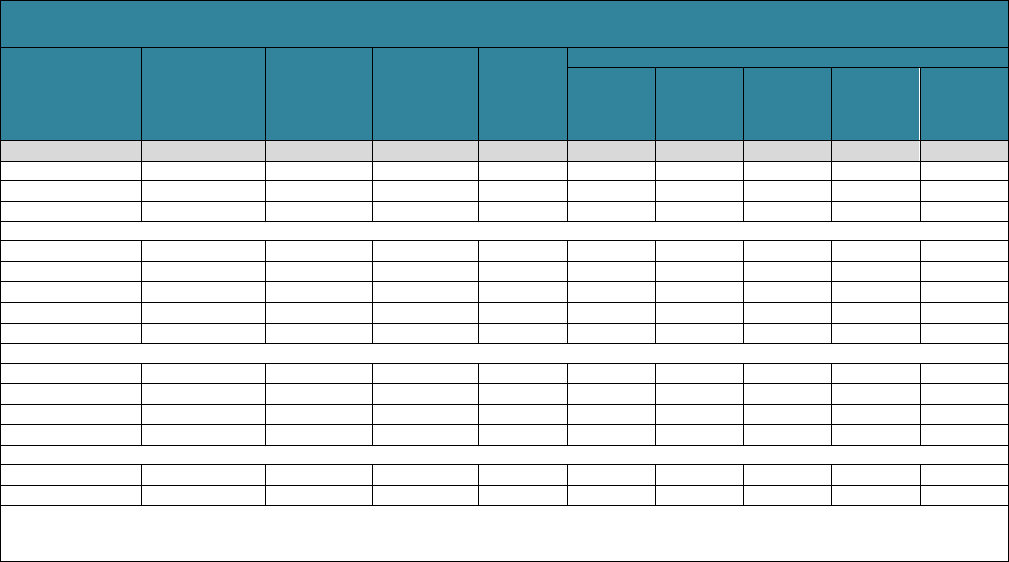

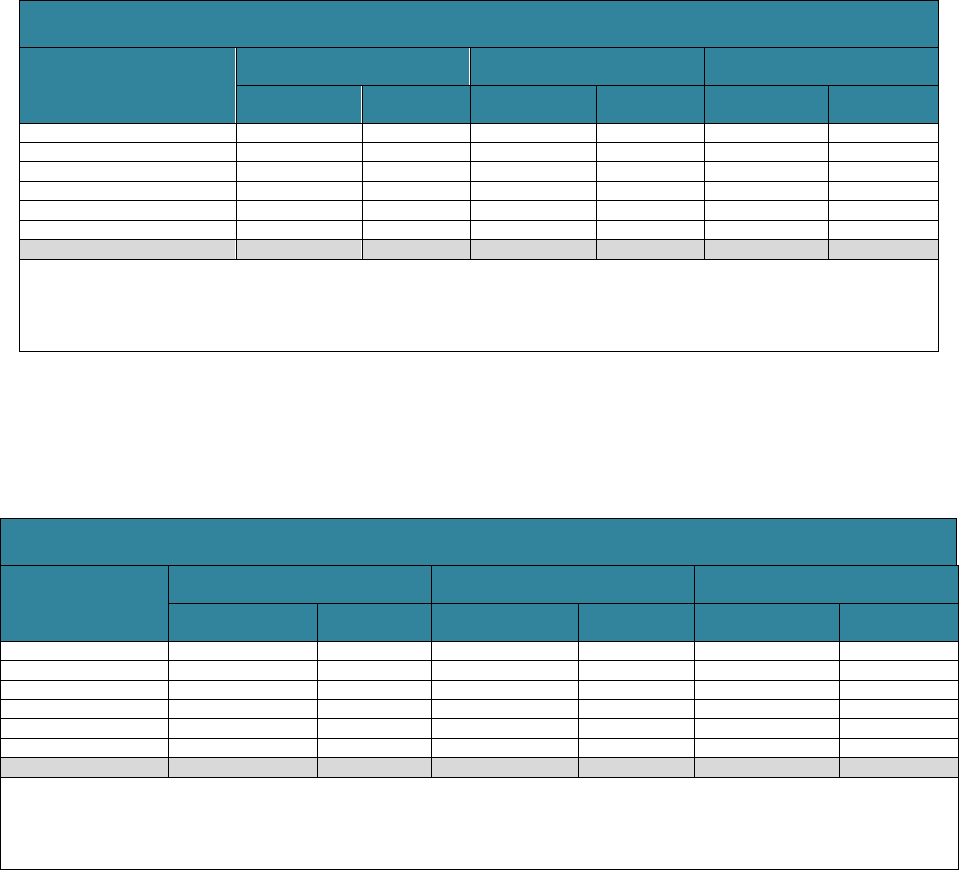

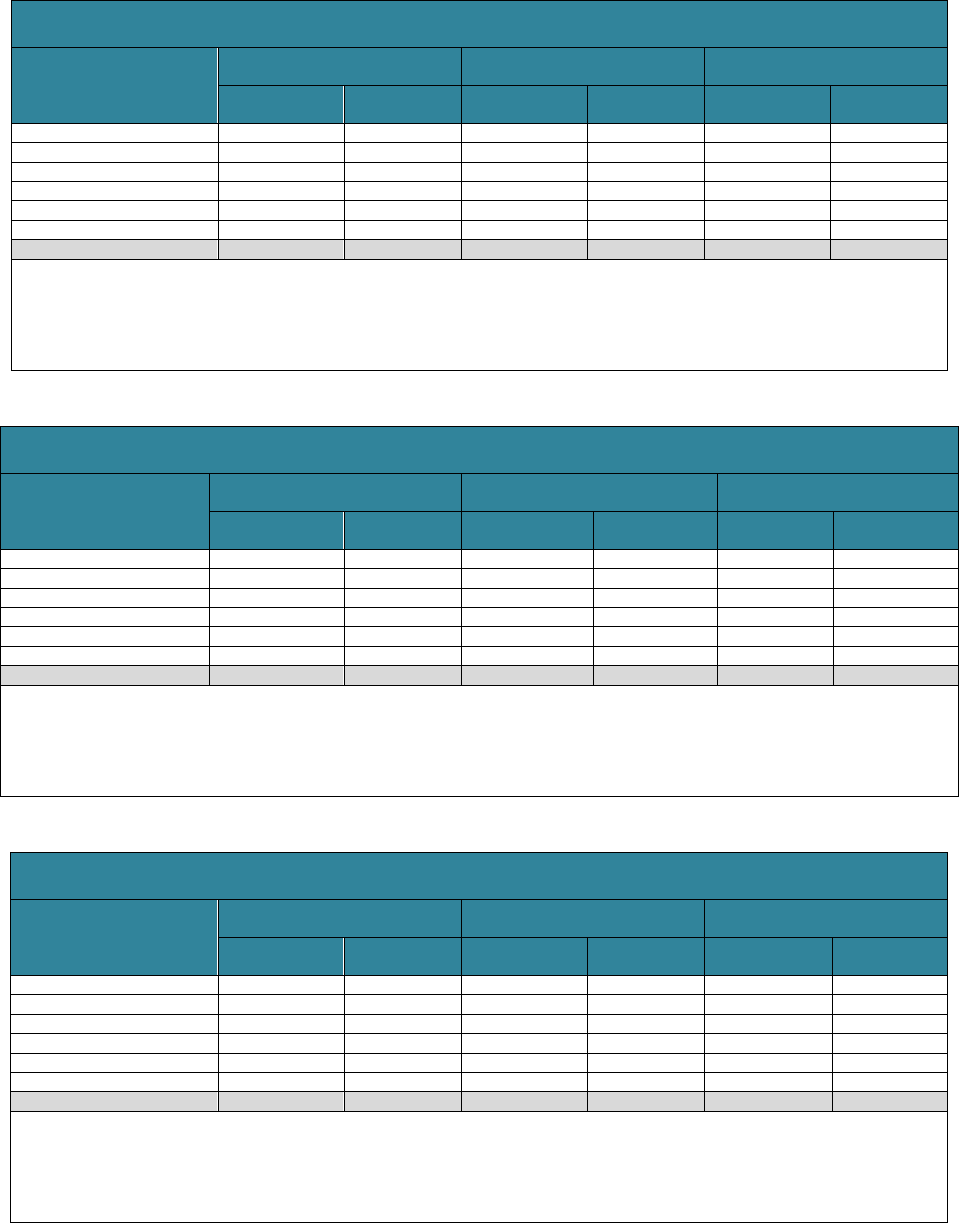

Table 1 displays expected LTSS needs from age 65 to death. It presents life

expectancy at age 65 and the mean and distribution of the duration of disability for

adults turning 65 between 2021 and 2025.

10

The typical person in this cohort who is

alive at age 65 can expect to live another 20.5 years. Fifty-six percent can anticipate

having at least some significant need for LTSS; 12% are expected to have needs that

last less than a year, and about 22% are expected to have needs that extend beyond

five years. Estimates such as these are sensitive to the definition of disability. Many

people whose disabilities do not reach higher levels of significance still need and use

LTSS. With a more expansive definition, such as one that includes those with one ADL

RESEARCH BRIEF | 5

limitation or only IADLs limitations without severe cognitive impairment, the number of

people with LTSS needs would be significantly higher (Freedman and Spillman 2014;

Kemper, Komisar and Alecxih 2005/2006).

TABLE 1. Projected Need for LTSS for People Turning 65 in 2021-2025,

by Gender, Income, Self-Reported Health Status, and Marital Status

Life Expectancy

at Age 65

(years, full

population)

Average

Years of

LTSS Need

(all)

Average

Years of

LTSS Need

Given Some

Need

Percent

with Some

LTSS

Need

Distribution of LTSS Needs for the Full Population (%)

None

<1 Year

1.00-1.99

Years

2.00-4.99

Years

>5 Years

Total

20.5

3.1

5.4

56.4

43.6

11.9

7.9

14.7

22.1

Gender

Men

19.1

2.5

5.1

48.6

51.4

11.2

7.1

12.8

17.5

Women

21.9

3.6

5.6

63.7

36.3

12.4

8.6

16.4

26.3

Income Quintile at Age 65

Lowest

18.2

3.8

6.1

62.9

37.1

12.0

7.8

14.5

28.6

Second

19.1

3.0

5.3

57.3

42.7

12.7

8.2

14.9

21.5

Middle

20.3

3.2

5.8

54.8

45.2

10.1

7.9

14.4

22.4

Fourth

21.0

2.7

4.9

54.3

45.7

11.5

8.4

15.0

19.5

Highest

23.2

2.8

5.1

54.0

46.0

12.8

7.2

14.5

19.6

Health Status at Age 65

Excellent

22.3

2.8

5.1

55.6

44.4

11.5

7.6

17.0

19.5

Very good

21.4

3.0

5.4

55.5

44.5

11.2

8.5

13.8

22.0

Good

20.4

2.8

5.2

54.1

45.9

12.3

7.4

14.1

20.3

Fair/poor

18.9

3.5

5.7

60.3

39.7

12.2

7.7

15.1

25.3

Marital Status at Age 65

Married

21.6

2.9

4.7

54.9

45.1

11.9

7.8

14.6

20.6

Unmarried

19.7

3.4

5.4

60.0

40.0

11.9

8.2

15.2

24.7

SOURCES: Authors’ tabulations from DYNASIM4, run id982

NOTES: LTSS need is defined as a need for assistance with at least two activities of daily living or supervision due to severe cognitive impairment that is expected to last

at least 90 days.

LTSS needs vary substantially by personal characteristics. The average duration of

disability is higher for women (3.6 years) than for men (2.5 years). Among women, 64%

are likely to develop a significant disability, and 26% will need at least 5 years of care.

The proportion needing at least five years of care is especially high among those in the

lowest income quintile at age 65 (29%)

11

and those reporting fair or poor health at age

65 (25%). Among those who ever develop a significant disability, the average duration

is 5.6 years for women and 5.1 years for men.

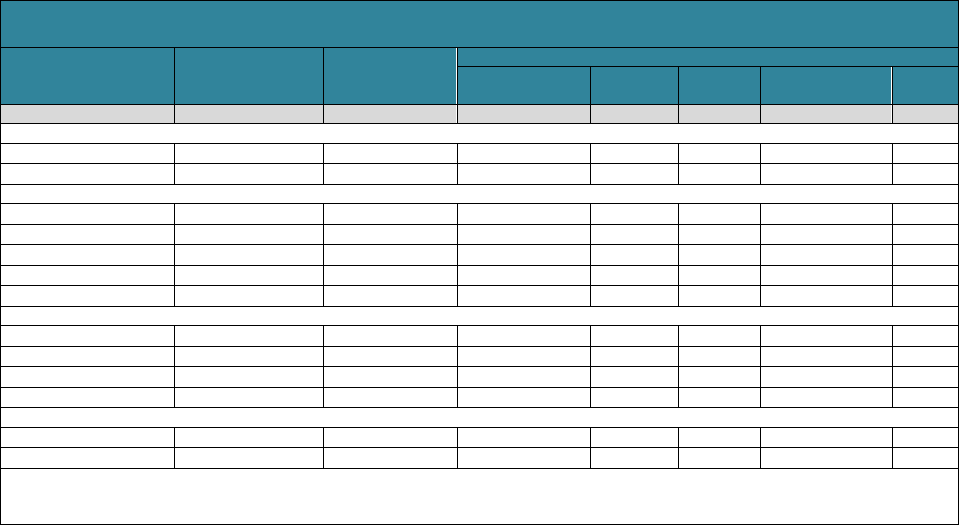

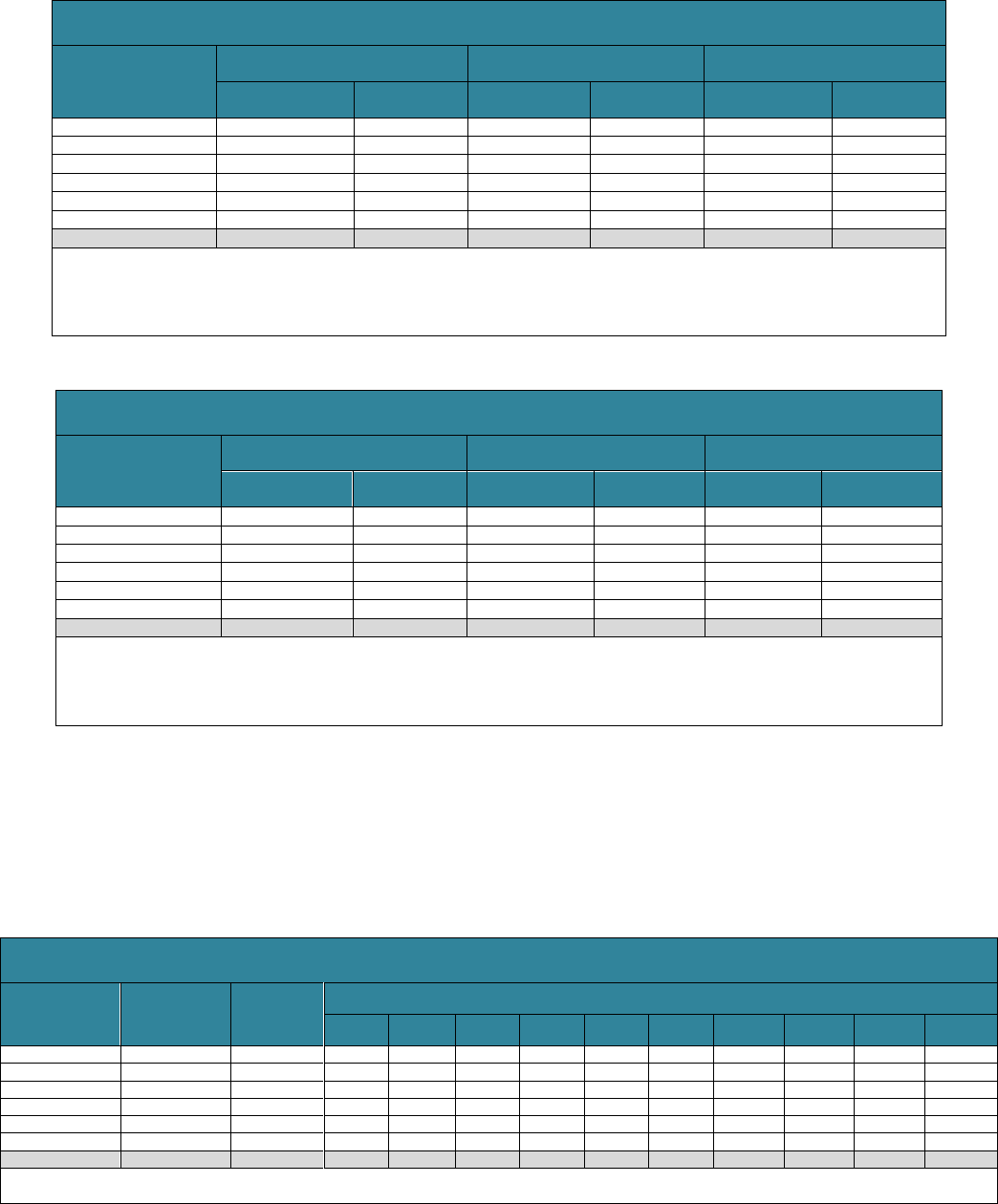

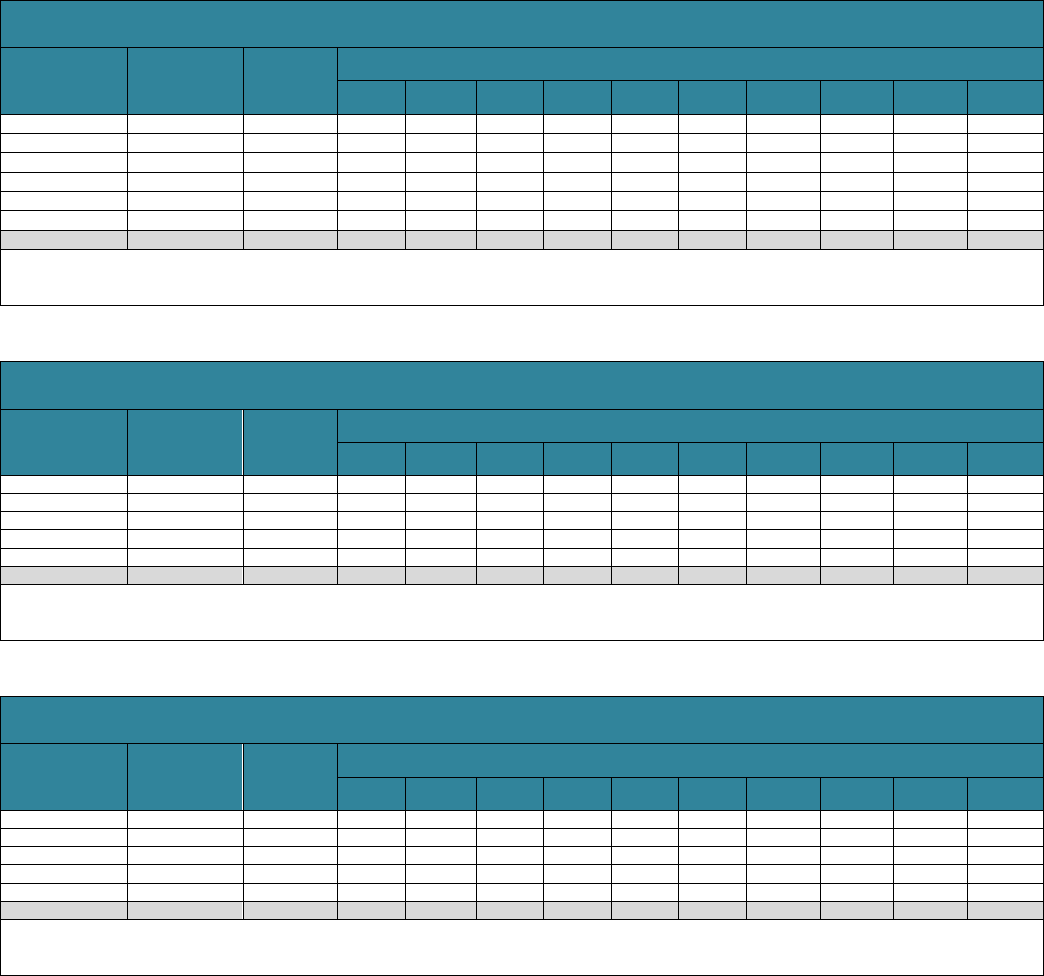

Table 2 examines the use of paid LTSS for a significant disability from age 65 onward

measured in service days (where 365 days of paid LTSS counts as one year,

regardless of whether all care occurs in the same calendar year). Of the average 3.1

years that older adults are projected to have a significant disability, they will receive paid

care for about 0.8 years, and unpaid caregivers, such as family and friends, will make

up most of the difference.

12

Again, patterns vary by personal characteristics. People

who are unmarried at age 65 use more paid services than those who are married (1.0

years, on average, compared with 0.7 years). Those in poor health at age 65 and those

with lower income at age 65, many of whom qualify for Medicaid, use more paid

services.

Distribution of LTSS Needs

for the Full Population (%)

Distribution of LTSS Needs for

the Full Population (%)

Distribution of LTSS Needs

for the Full Population (%)

Distribution of LTSS

Needs for the Full

Population (%)

RESEARCH BRIEF | 6

TABLE 2. Projected Use of Paid LTSS for People Who Turn 65 in 2021-2025, by Gender,

Income Quintile, Self-Reported Health Status, and Marital Status

Average Years with

Paid LTSS Use

Percent with Any

Paid LTSS Use

(all)

Distribution of Paid LTSS Use for the Full Population (%)

None

<1 Year

1.00-1.99

Years

2.00-4.99 Years

>5

Years

Total

0.8

45.3

54.7

24.1

7.3

9.5

4.4

Gender

Men

0.6

38.9

61.1

22.2

6.2

7.4

3.1

Women

1.0

51.3

48.7

25.9

8.4

11.4

5.6

Income Quintile at Age 65

Lowest

1.2

49.4

50.7

23.7

6.7

10.6

8.4

Second

0.8

45.6

54.4

26.1

6.7

8.5

4.3

Middle

0.7

44.7

55.3

25.2

6.3

9.3

4.0

Fourth

0.7

44.0

56.1

23.4

8.8

9.0

2.8

Highest

0.7

43.7

56.3

22.9

7.7

10.1

3.1

Health Status at Age 65

Excellent

0.8

46.1

53.9

23.1

8.6

10.9

3.5

Very good

0.8

45.5

54.5

25.0

7.1

9.1

4.3

Good

0.7

43.2

56.8

23.6

7.4

8.7

3.5

Fair/poor

1.0

47.1

52.9

24.3

6.8

10.2

5.8

Marital Status at Age 65

Married

0.7

42.5

57.5

23.4

7.1

8.7

3.4

Unmarried

1.0

50.5

49.5

25.9

7.9

10.9

5.9

SOURCES: Authors’ tabulations from DYNASIM4, run id982

NOTES: LTSS need is defined as a need for assistance with at least two activities of daily living or supervision due to severe cognitive impairment that is

expected to last at least 90 days.

While individuals on average will need 0.8 years of paid LTSS, 55% of older adults will

not use any paid LTSS. About 24% of older adults (or about half of paid LTSS users)

will receive less than a year of paid LTSS (measured in service days), and about 4% of

older adults will use five years or more. These projections are similar to Johnson’s

(2019) estimates of care use based on recent historical data.

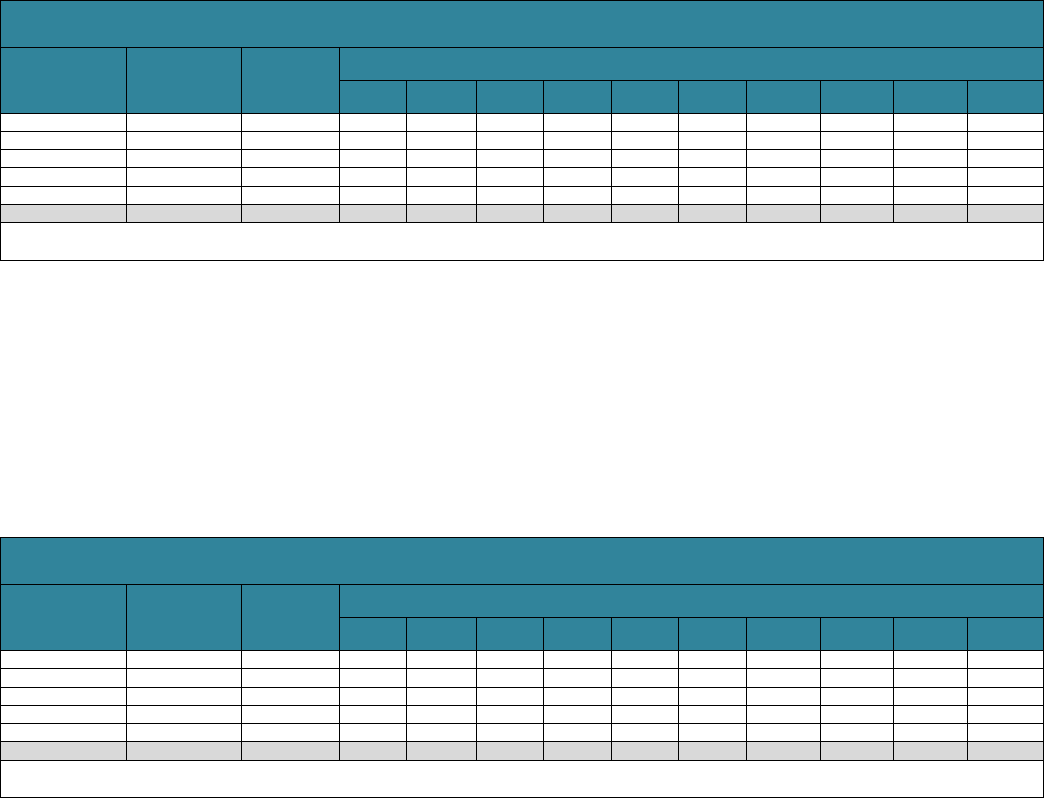

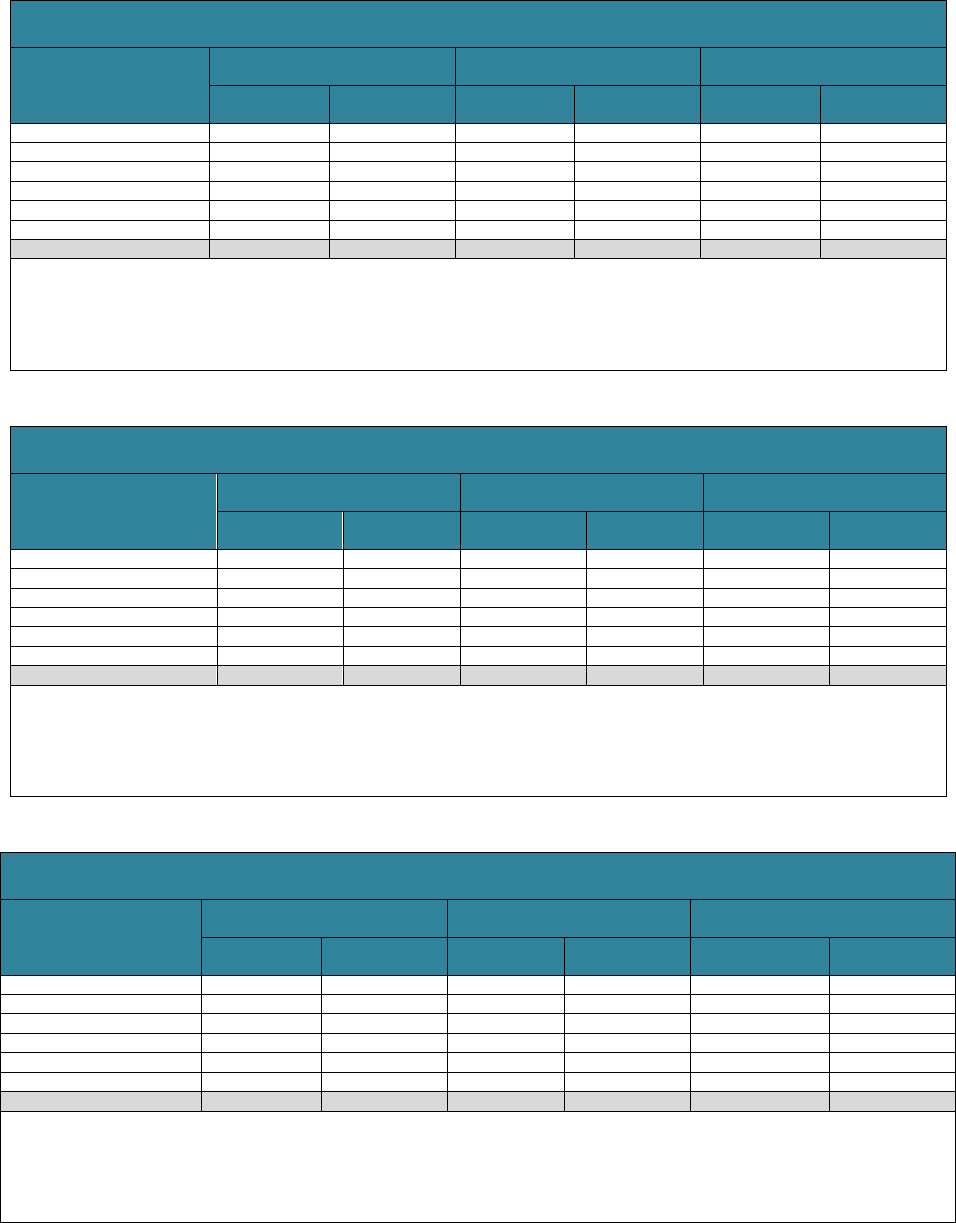

Table 3 presents the average sum of expenditures for LTSS (in 2020 dollars) that could

be expected from age 65 until death for the entire population, and Table 4 repeats the

analysis for those who use paid LTSS. The tables display this projected sum of

expenditures by setting and payer for those reaching age 65 between 2021 and 2025.

These estimates differ from a present discounted value (PDV) of expenditures at age

65, the amount that an individual would need to set aside at age 65 to cover future

LTSS expenses. The PDV is lower than the sum-of-expenditures measure because it

accounts for the investment returns that could be earned on funds set aside at age 65

until LTSS expenses begin, often after age 80. We show PDV projections in the

appendix.

13

We project that total paid LTSS expenses will average $120,900 per person (Table 3).

14

Medicaid is the largest payer of LTSS, averaging $51,800 after age 65 and accounting

for 43% of the total. Family out-of-pocket costs are also substantial, averaging $44,800

and accounting for 37% of the total. Payments vary by setting. Medicaid covers more

than half (52%) of total costs in institutional settings, whereas out-of-pocket payments

by families account for 44% of total community-based expenses.

15

Distribution of Paid LTSS Use for

the Full Population (%)

Distribution of Paid LTSS Use for the

Full Population (%)

Distribution of Paid LTSS Use for the Full

Population (%)

Distribution of Paid LTSS Use for

the Full Population (%)

RESEARCH BRIEF | 7

TABLE 3. Projected Sum of LTSS Expenditures from Age 65 through Death

for Adults Who Turn 65 in 2021-2025, by Payer and Setting

Payer

All Settings

Community-Based

(includes residential care)

Nursing Facility

Average ($)

Percentage

of total

Average ($)

Percentage

of total

Average ($)

Percentage

of total

Public

$70,100

58

$27,100

48

$43,000

67

Medicaid

51,800

43

18,600

33

33,200

52

Other Public

18,300

15

8,500

15

9,800

15

Private

$50,800

42

$29,400

52

$21,500

33

Out-of-Pocket

44,800

37

24,800

44

20,100

31

Private Insurance

6,000

5

4,600

8

1,400

2

All Payers

$120,900

100

$56,500

100

$64,400

100

SOURCES: Authors’ tabulations from DYNASIM4, run id982.

NOTES: Estimates are reported in 2020 inflation-adjusted dollars. Residential care is included in community-based care, not

nursing-facility care. LTSS prices are state- and setting-specific, based on Genworth (2019), Hansen Hunter and Company PC

(2018), and other sources. Nursing home and residential care prices are adjusted for wage inflation; home care prices grow

with the average of wage and price inflation. Components do not always sum to totals because of rounding.

Among those who ever use paid LTSS after turning age 65, the average cost is

projected at $245,400 (Table 4). Although conditioning on the use of LTSS increases

average costs, the cost distribution by payer and setting is very similar to that shown in

Table 3.

TABLE 4. Projected Sum of LTSS Expenditures from Age 65 through Death

for Users of Paid LTSS Who Turn 65 in 2021-2025, by Payer and Setting

Payer

All Settings

Community-Based (includes

residential care)

Nursing Facility

Average ($)

Percentage

of total

Average ($)

Percentage

of total

Average ($)

Percentage

of total

Public

$139,700

57

$52,500

46

$87,200

67

Medicaid

102,900

42

35,500

31

67,400

52

Other Public

36,800

15

17,000

15

19,800

15

Private

$105,700

43

$62,200

54

$43,500

33

Out-of-Pocket

93,500

38

52,800

46

40,700

31

Private Insurance

12,200

5

9,400

8

2,800

2

All Payers

$245,400

100

$114,700

100

$130,700

100

SOURCES: Authors’ tabulations from DYNASIM4, run id982.

NOTES: Estimates are reported in 2020 inflation-adjusted dollars. Residential care is included in community-based care, not

nursing-facility care. LTSS prices are state- and setting-specific, based on Genworth (2019), Hansen Hunter and Company PC

(2018), and other sources. Nursing home and residential care prices are adjusted for wage inflation; home care prices grow with the

average of wage and price inflation. Components do not always sum to totals because of rounding.

Expected LTSS costs are higher for women than men. Women’s costs average

$154,300 (Table 5), compared with $85,400 for men (Table 6). When we restrict our

analysis to adults with any LTSS expenditures, this average increases to $277,900 for

women and $200,400 for men (not shown). Women spend more on LTSS than men

because they tend to live longer and thus are more exposed to the risk of needing

LTSS. Additionally, married women are often younger than their husbands and more

likely to become widowed at older ages, leaving women less likely to receive unpaid

spousal care (and more likely to provide it).

All Settings

All Settings

Community Based

(Includes residential

care)

Community Based (Includes

residential care)

Nursing Facility

Nursing Facility

RESEARCH BRIEF | 8

TABLE 5. Projected Sum of Expenditures from Age 65 through Death,

for Women Who Turn 65 in 2021-2025, by Payer and Setting

Payer

All Settings

Community-Based (includes

residential care)

Nursing Facility

Average ($)

Percentage

of total

Average ($)

Percentage

of total

Average ($)

Percentage

of total

Public

$90,000

58

$33,200

47

$57,000

68

Medicaid

68,400

44

23,000

32

45,500

54

Other Public

21,600

14

10,200

14

11,500

14

Private

$64,300

42

$37,700

53

$26,600

32

Out-of-Pocket

56,400

37

31,400

44

25,000

30

Private Insurance

7,900

5

6,300

9

1,600

2

All Payers

$154,300

100

$70,800

100

$83,500

100

SOURCES: Authors’ tabulations from DYNASIM4, run id982.

NOTES: Estimates are reported in 2020 inflation-adjusted dollars. Residential care is included in community-based care, not

nursing-facility care. LTSS prices are state- and setting-specific, based on Genworth (2019), Hansen Hunter and Company PC

(2018), and other sources. Nursing home and residential care prices are adjusted for wage inflation; home care prices grow with

the average of wage and price inflation. Components do not always sum to totals because of rounding.

TABLE 6. Projected Sum of Expenditures from Age 65 through Death

for Men Who Turn 65 in 2021-2025, by Payer and Setting

Payer

All Settings

Community-Based (includes

residential care)

Nursing Facility

Average ($)

Percentage

of total

Average ($)

Percentage

of total

Average ($)

Percentage

of total

Public

$48,700

57

$20,600

50

$28,100

64

Medicaid

34,000

40

13,900

34

20,100

46

Other Public

14,700

17

6,700

16

8,000

18

Private

$36,700

43

$20,700

50

$16,000

36

Out-of-Pocket

32,600

38

17,800

43

14,800

34

Private Insurance

4,100

5

2,900

7

1,200

3

All Payers

$85,400

100

$41,300

100

$44,100

100

SOURCES: Authors’ tabulations from DYNASIM4, run id982.

NOTES: Estimates are reported in 2020 inflation-adjusted dollars. Residential care is included in community-based care, not

nursing-facility care. LTSS prices are state- and setting-specific, based on Genworth (2019), Hansen Hunter and Company PC

(2018), and other sources. Nursing home and residential care prices are adjusted for wage inflation; home care prices grow with

the average of wage and price inflation. Components do not always sum to totals because of rounding.

Table 7 presents the distribution of the sum of expected costs for adults ages 65 and

older in 2021-2025 by payer. About 15% of older adults can expect their total LTSS

expenses from age 65 onward to amount to more than $250,000, whereas about 8%

will have positive but low costs (less than $10,000). A smaller percentage (about 6%)

will spend $250,000 or more out of pocket on LTSS. Fourteen percent will spend at

least $100,000 out of pocket on LTSS after turning 65.

TABLE 7. Projected Average and Distribution of Sum of LTSS Expenditures from Age 65

through Death for Adults Turning 65 in 2021-2025, by Payer

Payer

Average

Expenditures

Percent of

People with

Expenditures

Distribution of Sum of LTSS Expenditures

(% of people)

None

<$10,000

$10,000-

$24,999

$25,000-

$49,999

$50,000-

$74,999

$75,000-

$99,999

$100,000-

$149,999

$150,000-

$199,999

$200,000-

$249,999

>$250,000

Public

$70,100

Medicaid

51,800

18.3

81.7

2.4

1.4

1.5

1.1

1.0

1.6

1.5

1.2

6.8

Other Public

18,300

40.9

59.1

13.2

8.6

8.1

3.8

2.2

2.4

1.0

0.6

0.8

Private

$50,800

Out-of-Pocket

44,800

34.9

65.1

5.9

5.0

4.4

3.2

2.3

3.7

2.3

1.6

6.4

Private Insurance

6,000

3.6

96.4

0.4

0.5

0.6

0.3

0.2

0.5

0.2

0.2

0.6

All Payers

$120,900

49.3

50.7

8.2

5.4

5.5

3.7

2.7

3.8

2.9

2.4

14.7

SOURCES: Authors’ tabulations from DYNASIM4, run id982.

NOTES: Estimates are reported in 2020 inflation-adjusted dollars.

A

ll Settings

Community-based (Includes residential care) Nursing Facility

A

ll Settings

Community-based (Includes r

esidential care)

Nursing Facility

RESEARCH BRIEF | 9

These figures mask important differences by income. People with lower incomes tend

to have more of their costs covered by Medicaid and pay less out of pocket. The

DYNASIM4 projections suggest that although Medicaid is used by older adults

throughout the age-65 income distribution, it primarily serves those in the bottom two

income quintiles (Table 8). For example, about 35% of people in the bottom income

quintile at age 65 and 23% of those in the second quintile will receive Medicaid LTSS at

some point after turning 65, compared with 6% in the top income quintile. Our

projections indicate that adults in upper income quintiles who use Medicaid are typically

individuals who have survived through their mid to late 90s, consistent with other

research (Borella et al. 2017; DeNardi et al. 2013).

TABLE 8. Projected Average and Distribution of Sum of Medicaid LTSS Expenditures

From Age 65 to Death for Adults Who Turn 65 in 2021-2025, by Income Quintile

Income Quintile at

Age 65

Average

Medicaid

Expenditures

Percent of

People with

Medicaid

Expenditures

Distribution of Sum of Medicaid LTSS Expenditures

(% of people)

None

<$10,000

$10,000-

$24,999

$25,000-

$49,999

$50,000-

$74,999

$75,000-

$99,999

$100,000-

$149,999

$150,000-

$199,999

$200,000-

$249,999

>$250,000

Lowest

108,400

35.4

64.6

4.4

2.8

2.4

1.7

1.7

3.6

2.4

2.1

14.3

Second

63,500

22.5

77.5

3.4

1.8

1.7

1.5

1.1

1.7

2.0

1.6

7.6

Middle

47,600

17.6

82.4

2.5

1.4

1.4

1.1

0.9

1.1

1.7

1.2

6.4

Fourth

21,400

9.3

90.7

1.2

0.3

1.4

0.6

0.4

0.9

0.8

0.7

3.1

Highest

14,000

5.7

94.3

0.4

0.4

0.4

0.4

0.6

0.6

0.4

0.2

2.3

All Quintiles

$51,800

18.3

81.7

2.4

1.4

1.5

1.1

1.0

1.6

1.5

1.2

6.8

SOURCES: Authors’ tabulations from DYNASIM4, run id982.

NOTES: Estimates are reported in 2020 inflation-adjusted dollars.

Family out-of-pocket expenditures, in contrast, are more concentrated within higher

income quintiles (Table 9). The average lifetime out-of-pocket LTSS expense in the top

quintile is $75,400, compared with $15,400 in the bottom quintile. Again, however, the

mean obscures important distributional information. About 10% of people in the top

income quintile at age 65 can expect to incur out-of-pocket expenses after turning age

65 that exceed $250,000. In the bottom half of the income distribution, where more

people are protected by Medicaid, the expected share with out-of-pocket spending that

exceeds $250,000 is less than 5%.

TABLE 9. Projected Average and Distribution of Sum of Family Out-of-Pocket LTSS Expenditures

from Age 65 to Death for Adults Turning 65 in 2021-2025, by Income Quintile

Income Quintile at

Age 65

Average

Out-of-Pocket

Expenditures

Percent of

People with

Out-of-Pocket

Expenditures

Distribution of Sum of Out-of-Pocket LTSS Expenditures

(% of people)

None

<$10,000

$10,000-

$24,999

$25,000-

$49,999

$50,000-

$74,999

$75,000-

$99,999

$100,000-

$149,999

$150,000-

$199,999

$200,000-

$249,999

>$250,000

Lowest

15,400

27.6

72.4

5.3

4.7

4.1

2.0

1.9

3.4

1.8

1.0

3.4

Second

34,200

32.9

67.1

6.2

4.5

4.2

4.4

2.3

3.8

1.9

1.2

4.4

Middle

43,200

34.7

65.3

6.1

4.8

4.7

3.5

1.5

3.9

2.0

1.9

6.3

Fourth

57,900

38.1

61.9

6.2

5.7

4.4

2.9

2.5

3.7

2.8

2.0

7.9

Highest

75,400

41.5

58.5

5.6

5.6

4.7

3.5

3.3

3.7

3.1

1.9

10.3

All Quintiles

$44,800

34.9

65.1

5.9

5.0

4.4

3.2

2.3

3.7

2.3

1.6

6.4

SOURCES: Authors’ tabulations from DYNASIM4, run id982.

NOTES: Estimates are reported in 2020 inflation-adjusted dollars.

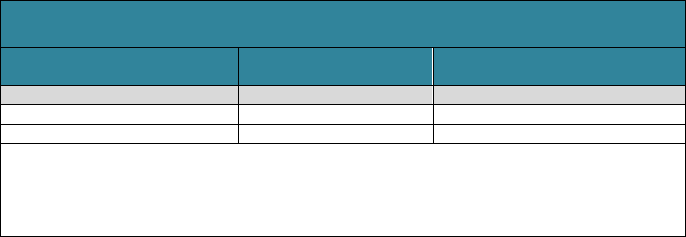

Many older adults with care needs receive substantial amounts of unpaid care from

family members and friends. Our projections indicate that the value of unpaid family

care received by adults born between 2021 and 2025 with significant disabilities

averages $91,900 (Table 10). Among people receiving unpaid family care, the average

value of care reaches $204,000, more than the value of all paid LTSS. Women receive

more unpaid care than men.

RESEARCH BRIEF | 10

TABLE 10. Projected Average Value of Unpaid Family Care from

Age 65 through Death for Adults Who Turn 65 in 2021-2025

All Adults

Adults Receiving Unpaid

Family Care

Total

$91,900

$204,000

Men

74,200

196,800

Women

108,600

208,800

SOURCES: Authors’ tabulations from DYNASIM4, run id982.

NOTES: Estimates are reported in 2020 inflation-adjusted dollars and restricted to care

received during periods of significant disability. Each hour of unpaid care is valued at the

median hourly wage for home care workers in the care recipient’s state of residence and

summed from age 65 to death.

Conclusion

Most Americans who survive to age 65 can expect to need and use LTSS. Our

estimates suggest more than half the population (56%) will have a significant level of

disability. On average, the projected duration of LTSS need is 3.1 years, and the

projected length of paid LTSS is just less than one year. The average cost of this care

is $120,900. However, a number of people can expect to need LTSS for many years

and to have care costs that total hundreds of thousands of dollars. Average long-term

care costs can be out of reach for many Americans. Medicaid is an important payer of

LTSS, but because it serves only those who meet strict income and asset criteria many

families pay for LTSS out of pocket. Private LTSS insurance has only a modest reach,

and it predominantly covers costs for those high in the income distribution. Other public

expenditures, such as U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) care, only help cover

small shares of the population with LTSS needs. The value of unpaid care provided by

family members and friends to people with significant disabilities exceeds the value of

paid care, and unpaid care is even more important when people have less severe

disability. Our results highlight the need for better planning for LTSS to accommodate

both average and catastrophic financial risks associated with chronic disability.

Differences from Earlier Projections

The results presented here differ from those reported in Favreault and Dey (2016).

Compared with the earlier version of our model, which generated Favreault and Dey’s

projections, our updated model projects longer average durations of LTSS needs (3.1

years versus 2.0 years), but the average time spend receiving LTSS does not differ

much between the two versions. The updated model also projects lower average LTSS

expenditures ($120,900 versus $138,100), especially for family out-of-pocket payments.

These differences result from some definitional changes between the two analyses and

numerous technical changes and updates.

An important substantive change between this brief and Favreault and Dey (2016) is

that we removed from our expected cost tables the incidental LTSS that Medicare

covers. As Box 1 discusses, Medicare generally does not pay for long-term care when

it is the only service a person needs. However, some people may have some of their

LTSS needs met through the course of receiving post-acute care. Given recent

Medicare payment rule changes, we expect that this type of overlap will be less

common in coming years.

RESEARCH BRIEF | 11

Much of the shift in the projections result from data updates and changes in the way we

specified model equations. We updated the DYNASIM starting sample to rely on later

panels of the Survey of Income and Program Participation. We also use more recent

state-specific price data (Genworth 2019, Hansen Hunter and Company 2018). Further,

we re-estimated many of the model parameters so that they use more recent data from

the Health and Retirement Study and other data sources. As we re-estimated some

parameters, we sometimes changed equation specification, which altered our

projections. These changes increased families’ sensitivity to costs when making LTSS

decisions, reducing some paid LTSS use by lower-income families, especially when

they would have to pay out of pocket. They also reduced service use at older ages.

When projecting the duration of LTSS needs, we now focus more on days in need

rather than years in need to better capture partial-year impairments. Additionally, we

removed some post-acute services from our LTSS estimates and improved our

algorithm of assigning costs to payers, which increased the significance of other public

payers, such as the VA and programs funded by the Older Americans Act.

In addition, the updated model improves our projections of severe cognitive impairment,

which partly determines the projected population with significant disabilities at risk of

receiving LTSS. We closely compare our dementia projections with the literature on the

distribution of the duration of impairment (for example, Brookmeyer et al. 2002, Larson

et al. 2004). Although the literature on cognitive impairment has been growing rapidly in

recent years, estimates on the length of time with a severe cognitive impairment is still

limited. As more data become available and this literature evolves, we will continue to

update these functions, given that dementia is such a significant driver of the need for

LTSS, and especially paid care.

Despite these differences, our substantive conclusions remain unchanged: older adults

face significant risk of needing LTSS, potentially incurring large out-of-pocket costs and

requiring unpaid help from family members.

End Notes

1. LTSS is also sometimes called long-term care.

2. Services may be provided in a person's home, in the community, or in residential

facilities (e.g., nursing homes or assisted living facilities) (Office of the Assistant

Secretary for Planning and Evaluation 2012).

3. Most LTSS is not medical care, but rather help with basic personal tasks of

everyday life. Medicare does not cover this LTSS (also called custodial care) if

that is the only care needed. Most nursing home care is custodial care. Medicare

does cover care in a hospital, skilled nursing care in a skilled nursing facility,

eligible home health services, and hospice and respite care.

RESEARCH BRIEF | 12

4. In a recent representative survey of Americans aged 40-70 conducted by GfK on

behalf of the Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation at the

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, only 25% of respondents

correctly identified Medicaid as the government program that pays the most for

LTSS in the United States.

5. The ADLs enumerated in the statute are eating, toileting, transferring, bathing,

dressing, and continence.

6. Throughout the brief we reference this level of need as “significant LTSS needs.”

7. DYNASIM4's LTSS projections draw information from a wide range of cross-

sectional and longitudinal sources, including the Health and Retirement Study,

Medicare Current Beneficiary Study, and National Health and Aging Trends

Survey.

8. Capturing trends in LTSS outcomes is challenging. When there is a clear trend,

such as the decline in mortality, DYNASIM4 follows the Social Security trustees'

assumptions. Otherwise, DYNASIM4 assumes that the underlying propensity to

develop LTSS needs or use LTSS continues at current levels, but that the

aggregate rates observed change as the composition of the population shifts. As

the population becomes better educated, for example, the model assigns the rates

for more highly educated adults to more people, but the rate for an adult with a

certain level of education does not change.

9. DYNASIM4 varies LTSS prices somewhat based on income, so that some lower-

income families use lower-cost providers--especially for home care--and some

higher-income families--especially those covered by LTCI--use higher-cost

providers.

10. Multiple cohorts are used to provide a sample that is large enough for

subpopulation analysis.

11. We define income quintile by income relative to the federal poverty level. This

measure recognizes that married couples need more resources than single adults

but acknowledges that shared living arrangements allow couples to economize, so

a couple needs less than twice as much as a single adult. The measure includes

earnings, pensions, Social Security, Supplemental Security Income, and asset

income (defined as the annuitized value of financial assets) received by individuals

and, if married, their spouses.

12. Use of unpaid services is substantial at both the HIPAA and non-HIPAA disability

levels, while use of paid services is more concentrated at the HIPPA level.

RESEARCH BRIEF | 13

13. Dollar amounts are rounded to the nearest $100, reflecting the inherent uncertainty

surrounding the projections. PDV estimates, which are reported in Tables A1-A9,

use the Social Security trustees' ultimate real interest rate of 2.5%. Because the

trustees assume long-range price growth averages 2.6%, this real discount rate is

equivalent to a nominal long-run discount rate of about 5.1%.

14. We restrict our cost estimates to people with significant disabilities, except that we

count nursing home care costs regardless of a resident’s disability status and we

count residential care costs for residents who report difficulty with at least two

ADLs (or are severely cognitively impaired), instead of requiring them to need

assistance with two or more ADLs. Because our cost estimates use a somewhat

less stringent disability requirement than our estimates of the receipt of paid LTSS,

our projection of the share of older adults with LTSS expenditures slightly exceeds

our projection of the share who receive any paid LTSS (49.3% in Table 7 versus

45.3% in Table 2).

15. The relative share of costs borne by different payers is sensitive to whether and

how residential care is incorporated into these projections. Some researchers

exclude from LTSS cost estimates the housing component of residential care,

which is included in our estimates. The NHEA exclude some related sectors

completely (Hartman, Kornfeld and Catlin 2010). Removing the housing

component of residential care or removing residential care completely reduces out-

of-pocket costs and families’ share of spending.

References

Board of Trustees, Federal Old-Age and Survivors Insurance and Federal Disability

Insurance Trust Funds (2021). 2021 Annual Report of the Board of Trustees of the

Federal Old-Age and Survivors Insurance and Federal Disability Insurance Trust Funds.

Washington, DC: Government Printing Office.

Boards of Trustees, Federal Hospital Insurance and Federal Supplementary Medical

Insurance Trust Funds (2019). 2019 Annual Report of the Boards of Trustees of the

Federal Hospital Insurance and Federal Supplementary Medical Insurance Trust Funds.

Washington, DC.

Borella M, De Nardi M, and French E (2017). Who Receives Medicaid in Old Age?

Rules and Reality. Fiscal Studies, 39(1): 65-93.

Brookmeyer R, Corrada M, Curriero F, and Kawas C (2002). Survival Following a

Diagnosis of Alzheimer’s Disease. Archives of Neurology, 59: 1764-1767.

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (2015). Your Medicare Coverage: Long-Term

Care. Baltimore, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

http://www.medicare.gov/coverage/long-term-care.html (accessed April 29, 2015).

RESEARCH BRIEF | 14

Cohen MA (2016). The State of the Long-Term Care Insurance Market. In Nordman,

EC. The State of Long-Term Care Insurance: The Market, Challenges and Future

Innovations. Kansas City, MO: National Association of Insurance Commissioners and

Center for Insurance Policy Research.

Colello KJ (2022). Who Pays for Long-Term Services and Supports? Washington, DC:

Congressional Research Service.

DeNardi M, French E, and Baily Jones J (2013). Medicaid Insurance in Old Age.

Working Paper 2012-2013. Chicago, IL: Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago.

Doty P (2017). Private Pay Home Care: New Models of Access and Service Delivery.

Public Policy and Aging Report 27(3): 111-120. doi:10.1093/ppar/prx021

Favreault M, and Dey J (2016). Long-Term Services and Supports for Older Americans:

Risks and Financing. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services,

Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation. http://aspe.hhs.gov/basic-

report/long-term-services-and-supports-older-americans-risks-and-financing-research-

brief.

Fossett J, and Burke C (2010). Medicaid Policy and Long-Term Care Spending: An

Interactive View. Albany, NY: Rockefeller Institute.

Freedman VA and Spillman BC (2014). Disability and Care Needs among Older

Americans. Milbank Quarterly, 92(3): 509-541.

Freundlich N (2014). Long-Term Care: What are the Issues? Princeton, NJ: Robert

Wood Johnson Foundation.

Genworth (2019). Cost of Care Survey, 2019: Median Cost Data Tables.

https://pro.genworth.com/riiproweb/productinfo/pdf/282102.pdf.

Grabowski D, Feng Z, Intrator O, and Mor V (2004). Recent Trends in State Nursing

Home Payment Policies. Health Affairs, 23(1).

Hado E, and Komisar H (2019). Long-Term Services and Supports. Washington, DC:

AARP Public Policy Institute. https://www.aarp.org/content/dam/aarp/ppi/2019/08/long-

term-services-and-supports.doi.10.26419-2Fppi.00079.001.pdf.

Hagen S (2013). Rising Demand for Long-Term Services and Supports for Elderly

People. Washington, DC: Congressional Budget Office.

Hansen Hunter and Company PC (2018). A Report on Shortfalls in Medicaid Funding

for Nursing Center Care. Washington, DC: American Health Care Association.

https://www.ahcancal.org/facility_operations/medicaid/Documents/2017%20Shortfall%2

0Methodology%20Summary.pdf.

RESEARCH BRIEF | 15

Hartman MB, Kornfeld RJ, and Catlin AC (2010). A Reconciliation of Health Care

Expenditures in the National Health Expenditures Accounts and in Gross Domestic

Product. Suitland, MD: US Bureau of Economic Analysis.

https://apps.bea.gov/scb/pdf/2010/09%20September/0910_healthcare.pdf.

HomecarePulse (2019). Homecare Benchmarking Study 2019, Spring Edition. Rexburg,

ID.

Johnson R (2019). What Is the Lifetime Risk of Needing and Receiving Long-Term

Services and Supports? Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human

Services, Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation.

https://aspe.hhs.gov/basic-report/what-lifetime-risk-needing-and-receiving-long-term-

services-and-supports.

Johnson R (2022). Projections of the Risk of Long-Term Services and Supports at Ages

65 and Older. Report to ASPE. Washington, DC: Urban Institute.

Kane J (2013). PBS Newshour: Americans Seriously Unprepared for Long-Term Care,

Survey Finds. http://www.pbs.org/newshour/rundown/as-boomers-age-most-woefully-

unprepared-for-long-term-care/ (accessed May 5, 2015).

Katz S, Ford AB, Moskowitz RW, Jackson BA, and Jaffe MW (1963). Studies of Illness

in the Aged: The Index of ADL: A Standardized Measure of Biological and Psychosocial

Function. JAMA, 185(12): 914-919. doi:10.1001/jama.1963.03060120024016.

Kemper P, Komisar HL, and Alecxih L (2005/2006). Long-term Care over an Uncertain

Future: What Can Current Retirees Expect? Inquiry, 42: 335-350.

Kim JJ (2022). Personal Care Aides as Household Employees and Independent

Contractors: Estimating the Size and Characteristics of the Workforce. Innovations in

Aging, 6(1): 1-10.

Komisar H (2013). AARP Thinking Policy. http://blog.aarp.org/2013/08/22/medicare-

does-not-pay-for-long-term-care/ (accessed April 29, 2015).

Larson EB, Shadlen M-F, Wang L, McCormick WC, Bowen JD, Teri L, and Kukull WA

(2004). Survival after Initial Diagnosis of Alzheimer Disease. Annals of Internal

Medicine, 140(7): 501-511.

Mollica R (2009). State Medicaid Reimbursement Policies and Practices in Assisted

Living. National Center for Assisted Living, American Health Care Association.

National Association of Insurance Commissioners (2019). Long-Term Care Insurance

Experience Reports for 2018. Washington, DC: National Association of Insurance

Commissioners. https://naic.org/prod_serv/LTC-LR-19.pdf.

RESEARCH BRIEF | 16

Newquist DD, DeLiema M, and Wilber KH (2015). Beware of Data Gaps in Home Care

Research: The Streetlight Effect and Its Implications for Policy Making on Long-Term

Services and Supports. Med Care Res Rev, 72(5): 622-640.

doi:10.1177/1077558715588437.

Ng T, Harrington C, Musumeci M, and Reaves E (2014). Medicaid Home and

Community-Based Services Programs: 2010 Data Update. Menlo Park, CA: Kaiser

Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured.

Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation (2012). Glossary of Terms.

Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the

Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation. https://aspe.hhs.gov/glossary-terms

(accessed May 1, 2015).

Scism L (2015). Long-term Care Insurance: Is it Worth it? Wall Street Journal.

Schmitz A, and Giese C (2019). Is Insurance the Answer to the Long-Term-Care

Financing Challenge? Generations, 43(1): 86-88.

Stallard E (2011). Estimates of the Incidence, Prevalence, Duration, Intensity and Cost

of Chronic Disability among the U.S. Elderly. North American Actuarial Journal, 15(1):

32-58.

Tompson T, Benz J, Junius A, Nguyen K, and Lowell K (2013). Long-Term Care:

Perceptions, Experiences and Attitudes among Americans 40 or Older. Research

Highlights. Chicago: Associated Press-NORC Center for Public Affairs Research.

Ujvari K (2018). Disrupting the Marketplace: The State of Private Long-Term Care

Insurance, 2018 Update. Washington, DC: AARP Public Policy Institute.

https://www.aarp.org/content/dam/aarp/ppi/2018/08/disrupting-the-marketplace-the-

state-of-private-long-term-care-insurance.pdf.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (US DHHS) (2015).

LongTermCare.gov. http://longtermcare.gov/medicare-medicaid-

more/medicaid/medicaid-eligibility/ (accessed May 1, 2015).

VanDerhei J (2015). Retirement Savings Shortfalls: Evidence from EBRI's Retirement

Security Projection Model. Issue Brief. Washington, DC: Employee Benefit Research

Institute.

Warshawsky M (2014). Millionaires on Medicaid. Wall Street Journal.

Wiener J, Khatutsky G, Thach N, and Greene A (2015). What Americans Think About

Long-Term Care. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services,

Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation.

RESEARCH BRIEF | 17

Appendix: Projections of LTSS Expenditures Using a Present

Discounted Value Measure

TABLE A1. Projected PDV of Expenditures from Age 65 through Death

for Adults Who Turn 65 in 2021-2025, byPayer and Setting

Payer

All Settings

Community-Based

(includes residential care)

Nursing Facility

Dollars

Percentage

of total

Dollars

Percentage

of total

Dollars

Percentage

of total

Public

$42,200

60

$17,400

53

$24,800

67

Medicaid

31,500

45

12,400

38

19,100

52

Other Public

10,700

15

5,000

15

5,700

15

Private

$27,600

40

$15,600

47

$12,100

33

Out-of-Pocket

24,000

34

12,800

39

11,300

31

Private Insurance

3,600

5

2,800

8

800

2

All Payers

$69,800

100

$33,000

100

$36,900

100

SOURCES: Authors’ tabulations from DYNASIM4, run id982.

NOTES: PDV = present discounted value. Estimates are reported in 2020 inflation-adjusted dollars. We use a real discount rate

of 2.5% (5.1% nominal) in these calculations. Residential care is included in community-based care, not nursing-facility care.

LTSS prices are state- and setting-specific, based on Genworth (2019), Hansen Hunter and Company PC (2018), and other

sources. Nursing home and residential care prices are adjusted for wage inflation; home care prices grow with the average of

wage and price inflation. Components do not always sum to totals because of rounding.

TABLE A2. Projected PDV of Expenditures from Age 65 through Death

for Adults Who Turn 65 in 2021-2025 and Use Paid LTSS, by Payer and Setting

Payer

All Settings

Community-Based

(includes residential care)

Nursing Facility

Average ($)

Percentage

of total

Average ($)

Percentage

of total

Average ($)

Percentage

of total

Public

$83,700

59

$33,300

50

$50,300

67

Medicaid

62,200

44

23,400

35

38,700

52

Other Public

21,500

15

9,900

15

11,600

16

Private

$58,100

41

$33,600

50

$24,600

33

Out-of-Pocket

50,800

36

28,000

42

22,900

31

Private Insurance

7,300

5

5,600

8

1,700

2

All Payers

$141,700

100

$66,900

100

$74,800

100

SOURCES: Authors’ tabulations from DYNASIM4, run id982.

NOTES: PDV = present discounted value. Estimates are reported in 2020 inflation-adjusted dollars. We use a real discount rate

of 2.5% (5.1% nominal) in these calculations. Residential care is included in community-based care, not nursing-facility care.

LTSS prices are state- and setting-specific, based on Genworth (2019), Hansen Hunter and Company PC (2018), and other

sources. Nursing home and residential care prices are adjusted for wage inflation; home care prices grow with the average of

wage and price inflation. Components do not always sum to totals because of rounding.

TABLE A3. Projected PDV of Expenditures from Age 65 through Death

for Women Who Turn 65 in 2021-2025, by Payer and Setting

Payer

All Settings

Community-Based

(includes residential care)

Nursing Facility

Average ($)

Percentage

of total

Average ($)

Percentage

of total

Average ($)

Percentage

of total

Public

$52,800

61

$21,000

52

$31,900

69

Medicaid

40,400

47

15,100

37

25,300

55

Other Public

12,400

14

5,900

15

6,600

14

Private

$34,000

39

$19,400

48

$14,600

31

Out-of-Pocket

29,500

34

15,800

39

13,700

30

Private Insurance

4,500

5

3,600

9

900

2

All Payers

$86,800

100

$40,400

100

$46,400

100

SOURCES: Authors’ tabulations from DYNASIM4, run id982.

NOTES: PDV = present discounted value. Estimates are reported in 2020 inflation-adjusted dollars. We use a real discount rate of

2.5% (5.1% nominal) in these calculations. Residential care is included in community-based care, not nursing-facility care. LTSS

prices are state- and setting-specific, based on Genworth (2019), Hansen Hunter and Company PC (2018), and other sources.

Nursing home and residential care prices are adjusted for wage inflation; home care prices grow with the average of wage and price

inflation.

All Settings

All Settings

All Settings

Community Based Includes

Residential Car

e

Community Based Includes Res

idential Care

Community Based includes residential Care

Nursing Facility

Nursing Facility

Nursing Facility

RESEARCH BRIEF | 18

TABLE A4. Projected PDV of Expenditures from Age 65 through Death

for Women Who Turn 65 in 2021-2025 and Use Paid LTSS, by Payer and Setting

Payer

All Settings

Community-Based

(includes residential care)

Nursing Facility

Average ($)

Percentage

of total

Average ($)

Percentage

of total

Average ($)

Percentage

of total

Public

$93,000

60

$35,700

49

$57,300

69

Medicaid

70,900

45

25,400

35

45,500

54

Other Public

22,100

14

10,300

14

11,800

14

Private

$63,200

40

$37,100

51

$26,200

31

Out-of-Pocket

55,100

35

30,500

42

24,600

29

Private Insurance

8,100

5

6,600

9

1,600

2

All Payers

$156,300

100

$72,800

100

$83,500

100

SOURCES: Authors’ tabulations from DYNASIM4, run id982.

NOTES: PDV = present discounted value. Estimates are reported in 2020 inflation-adjusted dollars. We use a real discount rate

of 2.5% (5.1% nominal) in these calculations. Residential care is included in community-based care, not nursing-facility care.

LTSS prices are state- and setting-specific, based on Genworth (2019), Hansen Hunter and Company PC (2018), and other

sources. Nursing home and residential care prices are adjusted for wage inflation; home care prices grow with the average of

wage and price inflation.

TABLE A5. Projected PDV of Expenditures from Age 65 through Death

for Men Turning 65 in 2021-2025, by Payer and Setting

Payer

All Settings

Community-Based

(includes residential care)

Nursing Facility

Average ($)

Percentage

of total

Average ($)

Percentage

of total

Average ($)

Percentage

of total

Public

$30,900

60

$13,700

55

$17,300

65

Medicaid

22,000

43

9,600

38

12,500

47

Other Public

8,900

17

4,100

16

4,800

18

Private

$20,800

40

$11,300

45

$9,500

35

Out-of-Pocket

18,200

35

9,500

38

8,700

32

Private Insurance

2,600

5

1,800

7

800

3

All Payers

$51,700

100

$25,000

100

$26,800

100

SOURCES: Authors’ tabulations from DYNASIM4, run id982.

NOTES: PDV = present discounted value. Estimates are reported in 2020 inflation-adjusted dollars. We use a real discount rate of

2.5% (5.1% nominal) in these calculations. Residential care is included in community-based care, not nursing-facility care. LTSS

prices are state- and setting-specific, based on Genworth (2019), Hansen Hunter and Company PC (2018), and other sources.

Nursing home and residential care prices are adjusted for wage inflation; home care prices grow with the average of wage and price

inflation.

TABLE A6. Projected PDV of Expenditures from Age 65 through Death

for Men Who Turn 65 in 2021-2025 and Use Paid LTSS, by Payer and Setting

Payer

All Settings

Community-Based

(includes residential care)

Nursing Facility

Average ($)

Percentage

of total

Average ($)

Percentage

of total

Average ($)

Percentage

of total

Public

$70,500

58

$30,000

51

$40,600

65

Medicaid

49,900

41

20,700

35

29,300

47

Other Public

20,600

17

9,300

16

11,300

18

Private

$51,000

42

$28,700

49

$22,300

36

Out-of-Pocket

44,900

37

24,400

42

20,500

33

Private Insurance

6,100

5

4,300

7

1,800

3

All Payers

$121,500

100

$58,600

100

$62,800

100

SOURCES: Authors’ tabulations from DYNASIM4, run id982.

NOTES: PDV = present discounted value. Estimates are reported in 2020 inflation-adjusted dollars. We use a real discount rate

of 2.5% (5.1% nominal) in these calculations. Residential care is included in community-based care, not nursing-facility care.

LTSS prices are state- and setting-specific, based on Genworth (2019), Hansen Hunter and Company PC (2018), and other

sources. Nursing home and residential care prices are adjusted for wage inflation; home care prices grow with the average of

wage and price inflation.

All Settings

All Settings

All Settings

Community Based Includes residential care

Community

based includes residential care

Community Based includes residential care

Nurs

ing facility

Nursing Facility

Nursing Facility

RESEARCH BRIEF | 19

TABLE A7. Projected Average and Distribution of PDV of LTSS Expenditures from Age 65 through Death

for Adults Who Turn 65 in 2021-2025, by Payer

Payer

Average

Expenditures

Percent of

People with

Expenditures

Distribution of PDV of LTSS Expenditures

(% of people)

None

<$10,000

$10,000-

$24,999

$25,000-

$49,999

$50,000-

$74,999

$75,000-

$99,999

$100,000-

$149,999

$150,000-

$199,999

$200,000-

$249,999

>$250,000

Public

$42,200

Medicaid

31,500

18.3

81.7

3.0

1.8

1.7

1.5

1.3

1.9

1.6

1.2

4.3

Other Public

10,700

40.9

59.1

17.3

10.2

7.4

2.9

1.3

1.2

0.4

0.1

0.1

Private

$27,600

Out-of-Pocket

24,000

35.5

65.2

8.3

5.6

5.7

3.3

2.8

3.3

2.0

1.3

2.5

Private Insurance

3,600

3.6

96.4

0.6

0.7

0.6

0.5

0.3

0.3

0.2

0.1

0.4

All Payers

$69,800

49.3

50.7

10.4

6.4

6.9

3.7

3.2

4.3

3.0

2.4

9.0

SOURCES: Authors’ tabulations from DYNASIM4, run id982.

NOTES: PDV = present discounted value. Estimates are reported in 2020 inflation-adjusted dollars. We use a real discount rate of 2.5% (5.1%

nominal) in these calculations.

TABLE A8. Projected Average and Distribution of PDV of Medicaid LTSS Expenditures

from Age 65 to Death for Adults Who Turn 65 in 2021-2025, by Income Quintile

Income Quintile at

Age 65

Average

Expenditures

Percent of

People with

Expenditures

Distribution of PDV of LTSS Expenditures

(% of people)

None

<$10,000

$10,000-

$24,999

$25,000-

$49,999

$50,000-

$74,999

$75,000-

$99,999

$100,000-

$149,999

$150,000-

$199,999

$200,000-

$249,999

>$250,000

Lowest

71,625

35.4

64.6

5.4

2.8

3.2

2.4

2.8

3.6

2.3

2.7

10.2

Second

37,433

22.5

77.5

4.5

2.0

2.0

1.8

1.8

2.3

1.9

0.8

5.3

Middle

27,378

17.6

82.4

3.1

1.8

1.7

1.6

1.0

1.8

1.5

1.4

3.7

Fourth

11,463

9.3

90.7

1.2

1.5

0.9

1.0

0.5

1.2

1.3

0.5

1.1

Highest

6,904

5.7

94.3

0.5

0.6

0.8

0.8

0.4

0.6

0.8

0.5

0.7

All Quintiles

$31,517

18.3

81.7

3.0

1.8

1.7

1.5

1.3

1.9

1.6

1.2

4.3

SOURCES: Authors’ tabulations from DYNASIM4, run id982.

NOTES: PDV = present discounted value. Estimates are reported in 2020 inflation-adjusted dollars. We use a real discount rate of 2.5% (5.1%

nominal) in these calculations.

TABLE A9. Projected Average and Distribution of PDV of Family Out-of-Pocket LTSS Expenditures

From Age 65 to Death for Adults Turning 65 in 2021-2025, by Income Quintile

Income Quintile at

Age 65

Average

Expenditures

Percent of

People with

Expenditures

Distribution of PDV of LTSS Expenditures

(% of people)

None

<$10,000

$10,000-

$24,999

$25,000-

$49,999

$50,000-

$74,999

$75,000-

$99,999

$100,000-

$149,999

$150,000-

$199,999

$200,000-

$249,999

>$250,000

Lowest

6,021

28.9

72.5

7.1

5.4

4.2

2.8

2.3

2.5

1.7

0.9

0.6

Second

19,057

33.7

67.2

8.1

5.2

6.9

3.0

2.8

2.8

1.2

1.2

1.5

Middle

24,000

34.9

65.3

8.4

5.3

6.0

3.2

2.3

3.2

2.5

1.2

2.5

Fourth

31,577

38.5

61.9

9.6

5.4

5.3

3.7

3.3

3.5

2.4

2.2

2.7

Highest

40,737

42.0

58.5

8.2

6.7

6.3

3.9

3.1

4.6

2.4

1.2

5.0

All Quintiles

$24,029

35.5

65.2

8.3

5.6

5.7

3.3

2.8

3.3

2.0

1.3

2.5

SOURCES: Authors’ tabulations from DYNASIM4, run id982.

NOTES: PDV = present discounted value. Estimates are reported in 2020 inflation-adjusted dollars. We use a real discount rate of 2.5% (5.1%

nominal) in these calculations.

RESEARCH BRIEF | 20

This Research Brief, authored by Richard W. Johnson (Urban Institute) and Judith Dey (U.S. Department

of Health and Human Services), presents information about the risk of needing care and associated costs

to provide content for policymakers and others considering long-term care financing proposals.

The LTSS projections in DYNASIM4 were originally developed by Melissa Favreault when she was a

senior fellow at the Urban Institute. Her microsimulation skills, deep knowledge of long-term care policy,

and hard work made this brief possible. We are indebted to her leadership and insights.

The authors also gratefully acknowledge conceptual and modeling help from Owen Haaga, Paul Johnson,

and Brenda Spillman and valuable comments and advice from Lauren Anderson, Chris Giese, Harriet

Komisar, William Marton, Al Schmitz, Brenda Spillman, Anne Tumlinson, and the late Joshua Wiener.

Many advisory panel members and seminar participants helped refine our projections. This remains work

in progress that we will update regularly as new data become available.

This brief was prepared under contract #HHSP233201600024I between HHS’s ASPE/BHDAP and the

Urban Institute. For additional information about this subject, visit the BHDAP home page at

https://aspe.hhs.gov/bhdap or contact the ASPE Project Officers, at HHS/ASPE/BHDAP, Room 424E,

H.H. Humphrey Building, 200 Independence Avenue, S.W., Washington, D.C., 20201;

The opinions and views expressed in this report are those of the authors. They do not reflect the views of

the Department of Health and Human Services or Urban Institute.